Fly Away Peter, Fly Away Paul by Paul Kimm

Fly Away Peter, Fly Away Paul by Paul Kimm

I’m eighteen and it isn’t a good time between me and my mother. In turn that means it’s not good between me and my father. I am a very difficult, apathetic teenager. I am not helping around the home. I don’t do any chores and don’t see why I should. I believe I have an inherent right, for it can’t possibly have been earned, to be lazy. My age is not one for work, but for total rest I believe. My mother goes to work each morning. I don’t. She is a home help which means she goes to old people’s houses, flats, and bungalows and cooks and cleans a little for them, does bits of shopping they need, and tries to give them company during the allotted time the Health Service schedules her for. I stay at home watching television whilst she does this. She goes from home to home on her bicycle. Because of the shape of its frame its known as a woman’s or lady’s bicycle. On occasions I’ve ridden it I’ve felt physical embarrassment by the empty space between the seat and the handlebars where a man’s or gentleman’s bicycle would have a crossbar. I don’t like her bike, but I don’t own one of my own.

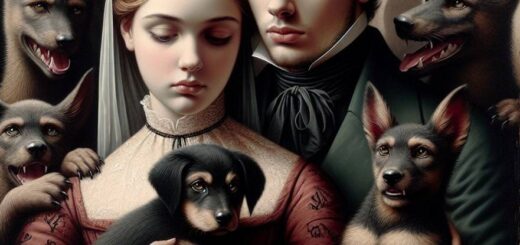

When she comes back from her morning shift each day, I have done nothing. On this day, the one I get thrown out, I have finished breakfast; three Weetabix and two slices of buttered toast. The bowl, spoon, small plate and knife I used are on the coffee table where I put them down after eating. They have remained there for two hours up to the point of my mother returning home. The milk carton I poured from onto my Weetabix is on the Formica countertop in the kitchen and not returned to the fridge. This is a daily occurrence. It is not the reason I get thrown out. I also haven’t walked our dog. I am asked each morning to take him out. Usually, I lie by saying I have. Most days I simply move his lead from the place the last family member who walked him left it to another place to trick my mother that the dog has been walked. Every day she can see I have not cleaned up after myself. Every day she sighs and calls me lazy. A useless layabout. I never respond, but in my head I agree with her. I enjoy my laziness. I am eighteen. It is not time for work in my life yet. Every day she asks me if I have walked the dog. I lie that I have, the moved dog lead being a daily effective deception.

The day I get thrown out its because my deception fails. I have ignored the dog’s whimpering at the back door. I have heard his whimpers, but I have ignored them. There has been no urge on my part to go to the toilet since breakfast, so I haven’t moved, but remained laid on the sofa with two cushions under the back of my head watching morning television. My mother is the one to discover that the dog has wet himself. His urine is puddled on the kitchen lino. He has also walked through his urine padding it into the hallway where there is carpet. This hallway carpet is quite new, and we always take our shoes off in our house. So, when my mother slips off her shoes, and steps the soles of her tights into the dog’s urine she realises I cannot have not walked the dog. She screams at me using short phrases like ‘for God’s sake’ and ‘I can’t take much more of this.’ When she walks into the living room, I’m still horizontal on the sofa. She is shouting at me. When I sit up to address her, I see she is also crying.

I respond to her upset with my usual denial of any sense of responsibility by declaring I had no way of knowing the dog needed the toilet. I say ‘no, I didn’t hear him at the door’. Another casual lie. I know my father will pop home soon for a sandwich break in the middle of his working day. I know he will erupt when he is told about my latest idleness. My mother has only just started shampooing the hallway carpet when he arrives. I stay in the living room whilst I hear her explain what’s happened and how upset she is with me. This is the point my father comes into the room and throws me out of the house. I know there is no question he means it. I must leave the family home immediately. The swear words he is using are the more serious ones. I’ve never heard him use them before. The words ‘fucking’ and ‘shit’ startle me as they leave his mouth. The sound of ‘fuck’ makes the acoustics in our living room seem changed. Outside the family I use these words all the time, but this is the first occasion I’ve heard this language in our house. When he tells me to get out, not come back, that I’m not welcome to live there anymore, it’s his use of these words that convinces me of his command.

I agree I’ll go, but I don’t apologise. I just say ‘okay, I’ll go’. It’s understood this is not an actual agreement. I am being ejected from our home. I slope up the staircase to the room I share with my eight-year-old brother and stuff some clothes into an old sports bag I haven’t used since leaving school two years earlier. I collect a couple of toiletry items and my toothbrush from the bathroom and put those in a plastic carrier bag, which I wrap up and put in the zip pocket of the sports bag. Once back downstairs I leave through the front door which we never use. We only ever use the back door for coming and going as do all our friends and family. Somebody knocking on the front door tells our family that we don’t know the person who has come to our house. It’s why I exit from the front door. I believe I’m making a point that I’m not part of the family anymore. As I close the door, I call out a sarcastic ‘okay, see you. I’m off.’

I walk down to the end of our street heading towards the seafront. Once I reach the North Beach I walk along the esplanade towards the harbour. I walk past the few stalls still open at this time of year. I inhale the sugar waft as I walk past the donut stand. Over the harbour bridge the cawing of seagulls grows louder as I approach the side where the trawlers dock. The smell changes from a sweet scent to the stench of ripe and pungent fresh fish. Sitting on the harbour wall I take in deep breaths of the newly brought in catches, then carry on to the South Side. The avenues on this side are populated with most of our town’s guesthouses. I read the names of those I walk past. The names the owners have chosen for them are either obvious like Beachcomber, Harbour Rest, Cliff House, or a foreign word such as Benneto, Edelweiss, or Shevilla. These two singular naming conventions of the local guesthouses occupy my mind as I make my way to the guesthouse my friend, Lee, lives in.

The DHSS office will pay for my rent in a guesthouse. It’s what Lee does. It is why I have come to see him. He has lived in Seaview Lodge for three months. I want Lee to introduce me to his landlady, the owner of Seaview Lodge, to ask if I can have a room. From what he has told me before I understand she will help me with the paperwork. I should be able to move in very quickly. He tells me the owner is happy to wait for the paperwork to go through as she always gets the housing benefit payment in the end. Living in the guesthouse with Lee I will have no dogs to walk or lie about walking. Dishes will be cleaned as part of the service. The bedding will be changed regularly, surfaces dusted, and carpets hoovered. I will eat twice a day, live in a warm room, with a television. It will cost me nothing. My laziness will be fully looked after.

Lee’s landlady is called Margaret Smith, but she insists that I call her Maggie or Ma, ‘like the other boys do’ she says. There is one room left for me which is ready to move into. It’s next to Lee’s room on the top floor. She shows me the room. It has a single bed with a floral quilt cover. The wallpaper is also floral, but a different pattern. There is a chest of drawers with a TV VHS combo on top of it, and a small wardrobe. From the dorma window there is a view across the street to another dorma window. Under the window is a small sink with a white radiator to the left of it. When she asks if I like the room, whether I want it, I say yes. It is agreed that I can move in there and then. I unpack whilst Margaret Smith goes downstairs to fill out the DHSS forms for me to sign later. The housing benefit claim will take two weeks, but she assures me the wait is no problem. Dinner will be at five. Liver and onions, with mash. A pudding for afters.

I go down to dinner with Lee. In the dining room there are two round tables with four chairs at each one. At just after five we are the final two lodgers to arrive in the dining room. Margaret Smith pops her head around the door and says that ‘dinner will be out in a minute boys.’ When she returns steam rises from the plates she brings out. As I watch the meals placed in front of the other lodgers, I notice we are all young men. Perhaps I am the youngest. I don’t think anyone is over thirty. As plates are received each man says, ‘thank you, Ma’ or ‘looks delicious, Ma.’ When my meal is put in front of me, I also say, ‘thank you, Ma’ and realise I have left a pause between ‘you’ and ‘Ma’ as I said it. Warmth fills my cheeks at this, and Margaret Smith puts her hand on my shoulder to rub it saying, ‘you’re welcome, son.’ I fork in the first mouthful. Then another. The food is thick, gooey, and soft. It is delicious.

When our puddings are finished Margaret Smith collects our emptied bowls. After all the bowls are taken nobody leaves their seat. When she comes back into the room, she says that the new lad can help her out with the dishes tonight. The others say thank you. Some go to the lounge part of the room and others up to their own rooms. Margaret Smith beckons me to follow her saying ‘that means you by the way’. In the kitchen, she explains a different boy helps out with the dishes each night and asks if I mind being chosen on my first night. I say I don’t. When she offers me the job of washing or drying, I reply ‘washing’. This is the first time I’ve washed dishes in many months. My stomach is full. I can still feel the rich taste of the food in my mouth. The warm suds in my hands are comfortable too. We don’t talk much whilst working together on the washing up. We are done in fifteen minutes. As she’s hanging up her tea towel Margaret Smith asks if I’ll have a chat with her in the lounge. I say ‘yes’.

The lounge is empty when we go through. The TV is switched off. I sit in one of the three armchairs. She sits on the sofa in the seat nearest to the armchair I’m in. Margaret Smith tells me I remind her of her son. I don’t know how to reply. She asks me if I’d like to see some photos of him. I nod my head to affirm I would with a high pitched ‘yes please’. I am lying. I don’t want to see photos of her son. She takes some framed photographs from the mantelpiece. In the black and white photos she is much younger. Next to her is a boy with white hair. I suppose his hair is blonde, but in the monochrome photo it is white. She tells me that it is ‘her Peter’ and mentions his and my names are the same as the two little birds that fly away and come back in that nursery rhyme. She repeats that I remind her of him. I ask her where he is now. She tells me he passed away when he was twelve. The photo we are looking at is the last one taken of him she informs me. He looks completely healthy in the photo. Perhaps Margaret Smith senses I am thinking this because she tells me he was a very sick boy even though you can’t tell in the picture. I say, ‘I’m sorry, Mrs Smith’. She reaches out her hand and clasps mine saying ‘please call me Ma, Paul. I’d like that. All the other boys call me Ma.’ I reply that I will do that from now on, then mumble how tired I am, and that I should turn in. She says ‘goodnight, Paul’ but I only say ‘goodnight.’

Upstairs Lee’s door is open. Noticing me walk past he calls me to come in. He says that I look like I’ve seen a ghost. I say I’m okay. He mentions that Ma is fine once you get used to her. She just likes to take care of us. He says, ‘were onto a good thing here, Paul.’ I reply that I know that. In my head I tell myself that ‘Ma’ is short for ‘Margaret’, that it doesn’t really mean ‘mother.’ Lee says a few more things about how it is good living at Seaview Lodge. He mentions she doesn’t skimp on food portions or the heating when it’s cold. He then suggests we watch a dirty tape he has. A mucky movie on VHS he keeps stashed at the back of his socks and underpants drawer. I don’t answer, but he puts it in anyway. He explains the sound needs to be very low because Ma can’t know he has it. He tells me to brace myself because I’ll have never seen anything so filthy in my life. He slaps my back and says ‘you’ll be having nightmares after this one.’ The tape clicks in, the flap closes, and I hear it whirring to start up.

There are three people standing at a bar. Two are women and one is a man. There is no barman in sight. The women are wearing sequin dresses. The man is wearing white trousers with a half unbuttoned black shirt. They are drinking cocktails. Another man walks in and goes to the woman on the left. They start kissing. After thirty seconds of kissing the woman kneels in front of the man, pulls down his trousers in front of her face and the back of her head moves forward and backward. The other woman goes to the other man and does the same. This continues for two minutes. The women stop and stand up. The men lift their dresses off them. They are naked underneath. The naked women kiss each other. The men watch this for twenty seconds without touching anyone. They then lift one of the women to the floor. The men go to the floor and touch and kiss the woman. They remove their shirts and now all four are naked. The other woman joins them, and the camera moves closer to their bodies. Only the moving skin of the four bodies is visible. Body parts, backs, arms, calves, chests, are not possible to tell apart until the camera reaches the kissing mouths and then moves down again to the four pairs of feet moving together. The camera moves up again. When it reaches their faces, they are not kissing. All eight eyes are closed, mouths open in what could be pain or pleasure. The camera moves back. The four bodies are entangled. Not moving. The screen fades to black.

Lee pauses it and asks if want to watch more. I have never seen anything like this, so I tell him I’m kind of tired. I am lying for the third time on this day. I don’t feel tired. He says that he understands but has a favour to ask. Tomorrow is the day his room gets cleaned. He doesn’t want Ma to find the tape. If I stash it somewhere in my room, then give it back to him after, it won’t be a problem he tells me. Rooms are cleaned twice a week and I only moved in a few hours ago. I reply that it’s no problem, as soon as his room is done just let me know. He says he doesn’t mind if I watch more, but it gets worse and into not sexy, but ‘mental stuff’. I don’t ask what happens, but as he gets up to eject the tape and wait for it to come out he informs me that there’s ‘mad bit with a dog’ in the next scene and later there are ‘people with nowt on just shitting’. He hands me the cassette. I can’t wait to shove it in the back of a drawer.

In my room I put the tape on top of the chest of drawers. I take off my jeans, trainers, and jumper. I fold the jeans first and put them in the top drawer of three. I fold the arms of my jumper across the front of it, then in half, and place it next to the jeans. Together, side by side, they fit the drawer perfectly. I look at them for a moment before closing the drawer. The tape is still on the top of the chest of drawers. I check the other drawers, the shelves in the wardrobe, and the space behind the base of the sink. I brush my teeth whilst I think about where to hide it. I spit into the sink, rinse my mouth with water from the cold tap. I decide under the bed is best. I lift the valance sheet that goes around the bed. There is only about an inch of space between the base of the bed and the carpet. I place the tape under the bed pushing it as far as I can. I wash my hands and face and get into the bed.

To help me sleep I make all the possible anagrams of four-letter words. I think about ‘seat’ and get ‘teas’, ‘eats’, and ‘sate’. I also remember ‘east’ and make ‘ates’, but I’m not sure that’s a word. I think about why ‘eats’ has an ‘s’ on the end but once it goes to the past it loses the ‘s’ and we can’t say ‘ates’. I say ‘he eats’, ‘she eats’, ‘they eat’, ‘I eat’ in my head. I say ‘he ates’, ‘she ates’, they ates’, ‘I ates’ too. I get fed up with ‘seat’ and try ‘love’. All I can get is ‘vole’. I try but can’t make anything else from ‘love’. I try to make a connection between ‘love’ and ‘vole’. With ‘seat’ I can connect its anagrams. He and she ‘eats’ sitting in a ‘seat’. He and she ‘eats’ when they are in a ‘seat’ and ‘sate’ themselves. We drink ‘teas’ sitting in a ‘seat.’ ‘Love’ and ‘vole’ have nothing to bind them. There is no connection between ‘love’ and a ‘vole’. I decide to make all sixteen possibilities with ‘love’ regardless of whether it’s an actual word or not. ‘Love’, ‘vole’, ‘evol’, ‘levo’, ‘elvo’, ‘veol’. I fall asleep before I cover all sixteen.

I sleep until ten in the morning getting woken up by Margaret Smith hoovering the landing outside mine and Lee’s doors. She knocks on my door. I get out of bed. Putting on my jeans and jumper, I call out ‘just a minute.’ She replies I can take my time and calls me ‘son’ again. When I open the door, she tells me she doesn’t mean to disturb, but I’ve missed my breakfast. She asks if everything is okay. I tell her it is, and she tells me to call her Ma again. Even though I moved in just yesterday she points out she’s still happy to give my room a clean. I thank her adding there is no need. I say I don’t mind keeping it clean by myself. Not to bother her with more work. When I motion to close the door, she pinches one of my cheeks and says, ‘I can’t tell you how much you remind me of my poor Peter.’ I don’t reply. She says something about getting all her work done. As she goes back to pick up her vacuum cleaner she sings, in a soft voice, ‘fly away Peter, fly away Paul.’

Lee is not in his room. I don’t want to stay in mine. I don’t want to go down to the lounge. I am standing between mine and Lee’s door. Looking down at my feet I see I haven’t put socks on yet. I return to my room and retrieve a grey pair that I have rolled up into a tight ball. Once unravelled I hold them up because I believe you can see which is left and right by the way the toes hang. I put the left on first and then the right. I brush my teeth leaning over the sink and rinse with water cupped in my palm. After putting on my shoes and jacket I listen at the door to check if I can hear Margaret Smith’s vacuum cleaner or any other sound from her. It is silent. I decide to go out for the day. I am not sure where to go. It is cold, but not raining and a long walk will be possible. I move down the stairs at a quick rate whilst trying to be quiet. When I reach the middle landing Margaret Smith is there, standing at a windowsill slowly dusting some porcelain animal ornaments she keeps on it. She turns to look at me and says she can make me some breakfast. I reply I don’t want to be any trouble and she replies she’ll feel better if I let her make me something. I decide agreeing to eat something is easier than discussing this with her. She replaces the pot rabbit she has in her hands and instructs me to follow her to the kitchen.

When we get in there she asks me what I would like and that I can have anything I want I reply I don’t want to be any trouble again. She says something I can’t quite catch about my ‘heart’s desire’ and I say something about being no trouble for a third time. She then offers to make what used to be her son’s favourite. It won’t take long. Treacle with something. She tells me how Peter had a sweet tooth and loved treacle on toast or pancakes and how it’d make her very happy if she could make me one of those. I realise toast will be faster, so I say, ‘toast please’. I stand near the exit to the kitchen as she goes about making it. She takes a sliced loaf from the bread bin and takes out two pieces. Whilst they are under the gas grill, she gets the butter and opens a cupboard, reaches up to the higher shelf, and takes down the green and gold tin of Golden Syrup. She turns the toast and watches it until it goes brown. Once its ready she butters it on the plate, then dips the same knife into the open jar of treacle, brings it next to the plate, lifts it out and lets the syrup drop from the knife to the toast in a long, slow liquid ribbon. After spreading it she hands it to me and says she hopes I like it as much as her Peter used to. She watches me as I take a bite from one corner. She is smiling and waiting for me to speak. I mumble is it okay if I take it with me. She says that’s fine. I put the two pieces together, hand her the plate, say ‘thank you’, and walk out of the room. I don’t say goodbye, but she says, ‘enjoy your treacle, son, and don’t forget to call me Ma.’

I walk straight out without taking another bite. As soon as I reach a litter bin, I throw the toast in it. The only other part I eat is to lick some of the dripped treacle off my fingers. I need to do something that will keep me outside all day. Some of the amusement arcades are still open this time of year. I decide against going across the harbour bridge, even though it’s the shorter route. Instead, I walk through the streets that lead to where the main arcades are. Joyland is the biggest and the only one open all year round. I head there. It’s quiet with only a few people playing on fruit machines. I hoped to be able to watch someone playing a video game, to spectate, but nobody is on one. I have a total of four pence in my pocket. Two twopenny coins. I decide to use them in the next two pence penny-pusher I walk past. I find one quickly and retrieve the first of the two coins. The first drop I make is poorly timed. The coin lands on top of another not managing to push any others. My next coin lands in a good position. It pushes two coins from the top sliding shelf to the bottom shelf. I watch the shelf retract and then return to push the fallen coins into the pile. They move some coins nearer the winning drop zone by a couple of millimetres. Nothing comes out.

Approaching back to Seaview Lodge I remember I haven’t eaten anything other than the corner of toast. This realisation gives me an instant hunger. It’s almost five o’clock. I know all the other lodgers will be in the dining room on time, so I won’t be on my own with Margaret Smith. I slow down anyway to make sure I get there a few minutes after five. Lee has saved the last seat for me next to him. He jokes something about me being the last one and shouts through to the kitchen ‘Ma, he’s here!’ She brings me a plate of sausage, egg, and chips with baked beans on the side. She also puts two slices of white bread in the middle of the table. She has cut them diagonally. A thick yellow stripe of butter is between the two slices, like an unfilled sandwich. I peel one triangle of bread and put two of the thick chips on the buttered side. I fold it into a sandwich. She is still standing there and says, ‘hope you won’t be late every day, Peter.’ She walks away before I can correct her. At the same time know I wouldn’t have done so, no matter how long she stayed standing at the table. I am grateful she’s gone. Lee, and the other two lodgers at my table, don’t seem to have noticed what she has called me.

I wolf down the rest of my food finishing before the others. I hope it doesn’t bring Margaret Smith’s attention to me, so I tell Lee that I’m full and won’t wait for pudding. He doesn’t seem bothered saying he’ll see me later to get that thing back off me. He forks another chip into his mouth and continues talking to the other two. Leaving the dining room, I need to exit onto the ground floor corridor which has the kitchen to the left where she is, with the stairs up to my room to the right. I walk fast whilst trying to keep my steps quiet on the carpet. When turning right out of the doorway I know my back is visible from the kitchen for about eight steps. I count them. On the fifth I hear ‘do you not want your pudding, Peter?’. I turn, shake my head, but don’t correct her again. I continue walking. She calls after me ‘Okay, son. I’ve cleaned your room by the way.’

I bolt up the stairs telling myself she calls everyone ‘son’, telling myself it’s just a slip. It’s because of that childish song about the two little birds, it’s just a slip. In my room the bedding has been changed for another flowery cover. I open my drawers. All my clothes have been rearranged, even my underpants and socks. My deodorant, toothbrush, and toothpaste have been moved from one side of the TV to the other, still in the mug I put them in. I can see the toothpaste tube has been squeezed down from the end to make the half near the nozzle plumper, like how my father has his. My empty sports bag, that I stuck in the bottom drawer of the bedside table, is now in the wardrobe. I look out of the dorma window across to the opposite dorma window. I clamp my palms on top of my head and massage my scalp. I push my fingertips hard into my skin. It occurs to me if I put my things back how they were in the first place I will feel better.

It only takes a few minutes to put it all how it was. The last thing I am doing is redistributing the toothpaste in its tube when Lee knocks at my door saying, ‘Let me in, Kimmbo.’ I open the door. He walks in and sits on my bed. He says he wants the tape back. He suggests watching some more of it with him if I like. Perhaps from the look on my face he says we don’t have to watch the ‘grim bits with the dog and shitting’. Because I don’t want to be alone in my own room, I agree to join him. I tell him it’s under the bed, and he stands up to let me get to it. Crouching down I reach under the bed, hoping I didn’t shove it too far so that we need to lift the bed up. My fingers can’t reach it. I can’t feel the plastic edge. I sweep my palm left and right across the carpet but can’t feel it. I ask Lee to help me lift the bed up. We hike it up so we can see the whole space under it, up to the skirting board on the other side. It’s not there.

‘What have you done with the fucking tape, Kimm?’ His hand is on my shoulder. It’s not where I left it, I tell him. I say that Mrs Smith has cleaned my room and moved stuff around. That it must be somewhere in the room. Between us we search every possible location the tape could be within a few minutes. It’s not in any drawer, or anywhere in the wardrobe. It’s not behind any of the furniture. We pad down every square inch of the bed cover. It’s not there. The tape has gone. Only me and Margaret Smith have keys to my room. Apart from me, Lee, and Mrs Smith, no one else even knows I’m living there. I haven’t been home. I haven’t told my mother and father where I am. I don’t have the tape in my room.

We discuss hypotheses about what else could have happened with the tape, but it comes back to the clear fact Ma has taken it. We go through lists of scenarios as to what she might do with it. Most of the ideas we come up with are to convince ourselves she won’t watch it. That she wouldn’t do that with our private property. I tell Lee it seemed a bit strange she used her dead son’s name to address me. He says he didn’t notice and reassures me that that means nothing. She’s like that. It’s how she is with names. She calls knives forks, the dining room the kitchen, and so on. Calling me Peter is calling a fork a knife. She’d be worse if she has watched it. There’s no way she’d speak to me at all if she’s actually had a look what’s on the tape. We speak for several hours. We don’t put on the TV to watch any channels. Some of our conversation attempts to move to other topics, but immediately comes back to what we think Ma has done with the tape. The only concrete decisions we make is that we can’t ask her about it and she can’t have watched it.

At breakfast the next morning she asks me how I want my eggs done. She doesn’t use any name with me. Neither Peter nor Paul. When she brings the food, she says ‘here you go, love’ to the other lodgers at my table, but doesn’t say anything as she places my two fried eggs and buttered toast in front of me. This reception, so different from how she greets the others, tells me she definitely has the tape. She not only has the tape but has watched some of the tape. I feel heat fill my face. One of the lodgers comments on my redness and I murmur that I don’t know why, maybe it’s just hot in the dining room. I eat one of the eggs. Lee is on the other table and hasn’t looked in my direction although I keep staring at him. I look down at the remaining food. The taste of yolk from the first egg is strong and rich in my mouth and on my tongue. I can’t eat more. I leave the table and return to my room to get a jacket and go for a walk along the beach.

As I come back down Lee is starting to come up the stairs. He asks me where I’m going, it’s raining, and cold, and there’s no reason to go out. I whisper, ‘she has it, Lee’. He says he’ll run up and get his coat to come with me. We walk with heads down, not speaking, hands in our jeans pockets. This doesn’t change for two minutes until we reach the end of the street which turns right towards the South Beach. Lee wants to know how I’m sure Ma has the tape. I explain to him how she was when she served breakfast. She didn’t say ‘love’ or ‘son’ like she does usually. He asks me if it’s possible she’s realised she used the wrong name with me and feels embarrassed. I tell him he’s clutching at another way to explain it, that we have to accept it. Lee explains he’s sorry, he can’t find somewhere else to live, that he likes it at Ma’s. He points out that she has found the tape in my room, not his. He says he’ll help me find a room in another guesthouse without needing a reference from Ma. The three days I’ve spent there won’t matter. I can put it behind me. I don’t say anything about his suggestions. I know I can’t remain there. After an hour of walking away from it we turn around and go back to Seaview Lodge.

We take the stairs two at a time and go straight into our own rooms. As soon as I close the door, I see the black oblong of the VHS tape laid precisely in the middle of my bedspread. The shock of seeing it returns the same heat to my face. I stare at it for a moment before picking it up. When I do there is also an audio cassette under it. I don’t have any cassettes. I have some old records and a few CDs back at my mum and dad’s, no cassettes. It’s not mine. I don’t know why it’s there or what it is. I’m still holding the black VHS tape in my hand. I’m looking at the transparent cassette lying on the bed. It’s only a tape, but it has no place in my room. I have nothing to do with it. I have nothing to play it on. I leave it there and go to Lee’s room.

When he opens his door, I wave the VHS tape in front of his face. He smiles, bends over with his palms on his knees, letting out a sigh of relief. He says, ‘thank God, you’ve found it’. I realise he thinks I’ve simply found it myself and I explain to him how it’s turned up. He says ‘Jesus Christ’. Inside his room he wants to play it to check if she has actually watched it or not. I answer that I haven’t played it since he gave it to me. He knows which scene is next and sticks the tape into the combo VHS television. I don’t want to see it, but I am frozen sitting on his bed. He says the ‘bit with the dog should be next.’ The screen stays black. There is no sound. Lee ejects it and lifts the tape up to look through clear section to the spool. ‘Fuck’ he says and holds it up. I shake my head and he explains it’s been rewound to the start. He replaces it back in the slot, lets it begin, and then forwards through. He doesn’t stop forwarding. The tape is blank. The dirty tape has gone. I then tell him there is a cassette on my bed and I don’t know what it is.

Lee takes it off my bed. Neither of us have anything to play it on. He thinks at least one of the other lodgers has some kind of player, but we agree neither of us want to ask. We have to gain access to a cassette player we can listen to it on. Just not within the walls of Seaview Lodge. I can’t go home to where there is a hi-fi. Lee’s situation is the same. We exit the guesthouse. The cassette is in one of my pockets. The VHS is in one of Lee’s. We decide to go into the centre to see if there is anywhere we can play the audio. On the way there we walk past a black litter bin. Lee removes the now blank dirty tape from his pocket and deposits it in the bin. It’s the same bin I threw the treacle on toast in. As we continue he suggests we go to the top floor of the local department store. They allow you to listen to the systems there and we can ask to play the tape. It’s late night Thursday opening, so we can still get in. The guys working there let you use them a bit and don’t bother you.

Inside Dunns Department Store we take the lift to the third floor. The stereos and television section is on the left when you come out of the lift. We wander over and find a small cassette player with double decks in the corner. It’s one that you can record tape to tape on. There are no other customers around. Lee goes over to one of the store assistants and comes back after a quick couple of questions. He tells me the shop assistant told us to go ahead, and no problem. I fish the cassette out of my pocket and hand it to Lee. He presses eject on the left hand deck and it opens gently. He puts it in, turns the volume down to one, and clicks the play button. We both lean in to a speaker each. We wait for a minute. Two quiet voices come on. I ask Lee to turn it up slightly. The voices become clear enough, and we listen, our ears against the mesh of the speakers.

It’ll be nice to have your voice, Peter, for mummy, and for you. It’s not only that though, son. It’s a nice thing for us to do together. Do you want to say something into the cassette recorder, Peter? It feels funny, mum. What should I say? That’s totally up to you. We can just keep it going a little bit and then play it back before recording more. Okay, mum, it will be funny to hear our voices. I don’t really know what it’s going to sound like. Okay, let’s do a little funny interview and after that we’ll rewind it and have a listen. Ready? Ready. Okay, this is Margaret Smith interviewing her special guest, and son, Peter Smith. Question one, what’s your favourite toy? I don’t know, mum, I like all my toys. I can’t choose one. Let’s go for an easier one then, son. Question two, Peter, what’s your favourite food? That’s easy! Treacle pudding with custard. I could eat treacle every day for the rest of my life! Can we have it today, mum? Can we, mum? Mum? Sorry, Peter. Yes, let’s go and buy a tin of treacle pudding for our tea. I think that’s enough recording for now though. I’ll stop it here and we’ll have a listen to our voices. It’ll be a nice thing to keep. Then we’ll go to the shop and get that treacle pudding.

The voices stop. There is a shuffling sound and a click. After that it’s silent. Our faces are very close to one another. We let it play for another minute. We don’t speak. When we move our ears from the player after this minute we still don’t know what to say. Lee shakes his head and mutters. I think he is just repeating the word ‘Jesus.’ He ejects it and keeps it in his hand. We both stand up and Lee says ‘let’s not talk about it.’ He then asks if we can just go. I nod. When we get back to the lift there is a small litter basket next to it. Lee drops the cassette in there. We don’t look at one another. The lift delivers us back to the ground floor where we entered a quarter of an hour before. We walk out of Dunns. It’s only when we are round the corner from Ma’s house that Lee asks me if I’m leaving straight away. I say ‘yes.’

We walk upstairs together treading on the thick carpet so to not make a sound. When we get to the top floor Lee says he’s sorry about the dirty tape. It’s not his fault I reply then he goes into his room and closes his door. In my room I pile my clothes and toiletries into the sports bag. I leave the room and lock the door leaving the key in it, go downstairs, and out of the front door. I walk home working out ways to say sorry in my head. I go through how I’ll make my promises. I try to work out the best way to make my sentences. How I won’t move the dog’s lead anymore. I’ll walk him every day. As soon as I wake up, I’ll take him out. Give him a good long walk. I won’t leave things lying around. I’ll clean up. I’ll do dishes. I’ll do the dishes after every meal. I don’t mind washing or drying. If my mother wants to wash, I’ll dry. If she wants to dry, I’ll wash. I can wash and dry. I can do both. Whatever needs doing around the house, I’ll do it.

* * * * THE END * * * *

Copyright Paul Kimm 2024

This is a strange psychodrama; although I’m uncertain of its meaning, it certainly weirded me out. The MC is an unfeeling ne’er’ do well who regains a modicum of respectability, near the end, but he is thoroughly unlikable. He seems, however, completely self aware of his disreputable nature. Social Services in the U.K. seems something quite apart that in the states, which is interesting.. As usual, Paul, you have written an intriguing and thoughtful story.

Like how you have thrown the obstacle of the tape and Ma’s affection at Kimmie!