The Infinite, Invisible by John C. Cannon

The Infinite, Invisible

by John C. Cannon

The swollen capital had erupted the day before. Elections on the African continent are always dicey. But in this landlocked swath of nothingness, there had been little cause for concern before now – not much to fight over but sand and heat, Jack Bonner always told his friends and family at home.

But the day before, a tiny minority faction that no one in the outside world had heard of won a single seat in parliament and finished a far-off sixth in the first round of presidential voting. Somehow, they’d used that defeat as a springboard to seize power, backed by guns and money and intelligence from extremists who of late had turned all of the west-central bulge of Africa into a chessboard, as if daring the West to play. The faction’s leader quashed the paltry resistance that did arise from the regular military and moved into the presidential palace just hours after the coup began.

Now, gone from the streets were the sounds of haggling from the half-hearted merchants selling plastic junk from China and donated t-shirts from the U.S. Also absent was the full-throated socializing – the predictable rhythmic greetings that Bonner had come to understand at least superficially, the just-as-predictable jokes and laughter that he could almost recite from memory but did not understand. That was the real reason for commerce in a society that did not care about commerce, only the importance of community.

Bonner always preferred to walk than drive or be driven through the capital. The clamor and buzz of cars and motorcycles and livestock and people, the stench of overripe produce blending with the oily sweetness of frying cakes sizzling over wood fires – all the people going about their business as if this street was the center of the universe, and to them it was. The languages they spoke – Hausa, Zarma, Tamashek – to each person whose language they were, they represented a perfect encapsulation of the world around them, all of the tools they needed to define their lives.

Yes, his white skin made him an immediate anomaly. And yes, as he strolled to and from the clinic, thumbs tucked under his shoulder straps, he fielded stare after stare. “Anassara! Anassara!” children, and sometimes their parents, would yell at him, seized only by the impulse to point out and connect with something strange. Visitors sometimes felt this was harassment, but Bonner had come to see it as an irrepressible urge to connect.

In fact Bonner loved the access being a foreigner afforded him: He was privy to the minute lives unfolding in an unknown universe that most would never see, and he was in on the secret that their lives were anything but minute. He’d soon found that their passing interest in his bizarreness couldn’t be matched by their own infatuation with their own lives, the latest gossip, what was happening in their city and country. So often, after their passing interest, they’d fall back into their daily routines, and he was witness to it all.

But not today. Left behind was a bowel-twisting calm in the dusty capital. What little blood had been spilled was nowhere in evidence. Bonner made the 20-minute walk to his apartment. Nothing happened.

He flipped on the radio when he entered the second-floor flat. The voice coming through the speaker said that, as soon as Adamou Koumana took power on his new government’s orders, he had cancelled the constitutionally required runoff to decide who of the people’s top three choices would run the country. “The president” – Koumana put it simply – “has been chosen.”

The broadcast transitioned to a report of thousands of the city’s residents with their belongings packed into rice sacks and pots on the southbound road out of town. Those who could afford the fare had piled into bush taxis and beat-up trucks.

“The de facto public transport in this infrastructure-poor country has become a lifeline for those who no longer feel safe here,” the reporter said. Then suddenly, the ambient crush of humanity stopped. Silence.

“Helen? Helen?” came the voice of the host. “We seem to have lost connection with our reporter Niamey, where it sounds as though an exodus has begun. Tuesday’s near-bloodless coup has left Adamou Koumana in power, and yet thousands have begun to flee in apparent fear of the fundamentalist cleric’s consolidation of–”

With a “shwip” the radio crackled and sat expelling a monotone hiss on the bedside table. Turning each of the dials back and forth, he tried to coax the voice back. No luck.

A few moments later, someone knocked at the door and without waiting for an answer, several uniformed men burst through.

“Doctor, we must go,” the first soldier said, taking a hand off his wooden-stocked gun to motion toward the door. Bonner recognized the man as one of the guards from the embassy.

“How long are we going for? Do I need to pack a few things?”

“I am sorry, Doctor. There is no time.” The man’s French was slow and articulated. Then, softening, perhaps catching a bit of concern from Bonner, he said, “You’ll probably be back here soon. Just to be safe, for your own protection.”

Which was it? Bonner thought. Is this just a formality, or do I really need protection? There was no denying the sense of urgency in the man’s voice.

“Sir. We must leave,” the embassy guard said again, this time in English, as if that might be blunter. Bonner didn’t look up from his rucksack, shoveling in the last of his essentials – a fraying medical kit marked with a white cross, a light sweater he always carried during temperamental African cold seasons, and his bucket – a long travel wallet made by a Tuareg craftsman he’d befriended. It held a smattering of business and credit cards, notes from friends here and stateside, and a little pocket for coins and bent-cornered photographs with the faces of people he’d met in his life. A child at the clinic, one of the many who liked to follow him throughout the day as they waited for a sick sibling or parent to be seen, had once called it his “bucket,” observing that he seemed to carry a little bit of everything in it, and the name stuck.

“Where are we going?” Bonner asked.

“To the embassy, Doctor.”

“The embassy?” The looks he fielded from the dark faces surrounding him twisted his gut. He continued to gather his things despite the guard’s insistence, but he had quickened his pace.

“I knew the brass weren’t happy about me setting up my own clinics, but I didn’t figure I’d ever get a personal invitation from the ambassador herself,” Bonner said, hoping to chisel away some of the seriousness of the situation. No one laughed. A guard in the back – the only one without a uniform, as it turned out – had his wide eyes locked on Bonner. The man’s angular face added to the unsettling harshness in his gaze.

He suppressed an unfamiliar rising panic. Years in makeshift operating theaters had corked even the hint of these feelings. He had worked in conflict zones before, seen bodies blown apart, battled starvation, malaria, beriberi in his patients – all of whom stretched the limits of what could be called survivable.

Yet this pinch in his gut was unlike all of that. Perhaps it was just the anticipation, the possibility that what lay before him could all go very wrong. If they could just hang in this moment, it seemed, the terrible potentialities would never come to be. It felt like the first time he’d pressed a scalpel to living human flesh. But in surgery he was trained for what could transpire, and he’d learned to deal with that terror. The only resolution came in action, in moving forward and not dwelling on what might be.

He cinched his backpack, and the men began shuffling toward the door. He followed the leader and moved into the hallway. The closed door echoed behind him in the empty building. Even the garrulous clerk at the front desk had vanished. He was always there with his accented English greetings: “Allo, Dr. Jack! It’s hot today, sir! Shall I get a taxi?…No? Have a good day, sir!”

But stepping out of the building with his motley entourage, the once-humming streets were now populated by a lone dog that seemed as perplexed and nervous as Bonner was, its pointy head swinging from side to side to check what was coming up from behind its fraying tail.

Bonner watched the dog turn a corner and disappear, and the men began piling into the U.S. Government-plated Land Cruiser. The driver had left its engine running, and Bonner noted the unfamiliar, not-unwelcome rush of air-conditioned air battling the afternoon swelter outside. The man with the wide white eyes got in last, after Bonner, slamming the two rear doors to the ambulance-style truck. He was covered head to toe in robes except for his face, framed by a perfectly wrapped length of cloth that ended in a coil neatly atop his head. The man’s eyes held a purpose that those of his companions lacked.

The driver stomped on the gas pedal; no one exchanged words. Sweat had beaded on Bonner’s forehead, and he did his best to squeegee it off with the back of his thumb. A chill from the car’s air conditioning ran up the arms of his long-sleeved, loose-fitting shirt. He shuddered, his knees inadvertently tapping against the guard he sat facing.

He held his hand up to the soldier and said, “Pardon.” But the man was paying attention only to what was in front of them through the front windshield.

The ride to the embassy was only 15 minutes long. But the angles of the turns they had to take to reach the embassy now felt sharper and more desperate with no children playing along the streets’ edges.

Bonner turned to one of his guardians and started to say something in French he’d hoped would lighten the pall of anticipation hanging in the car, but a movement from the back of the car arrested the words in his throat. The man in the turban lifted up on his seat bones and lurched forward, his eyes wide.

The car approached the gate to the embassy and slowed to a stop. Normally, two or three American marines would be sitting out front waiting for visitors. But the shade structure fashioned from woven grass mats and arm-thick logs stood vacant.

The other men noticed the vacancy too and were twisting on the cramped benches in the truck to see why no one had come out to greet them or open the gate. Bonner caught one of the driver’s eyes in the corner of the rear-view mirror. There he found no confusion. Instead Bonner saw a gaze intent on something.

What happened next would stay garbled in his mind for some time. Bonner heard the gate to the embassy grind open a sliver, and a beret-clad soldier peered out at the car. The next thing Bonner felt was a warm spray on his cheek and the immediate sense that the cramped air in the truck was too big for the space it had previously occupied.

Three more concussive blasts, and now Bonner tasted slippery metal on his lips. The tall guard who had been sitting between Bonner and the back of the driver’s seat slumped into his lap; the machine gun he’d been cradling slipped from his grasp, hanging only from a finger stuck through the trigger guard.

The fog clouding Bonner’s perception of what was happening began to lift. His eyes moved from the damp bleeding man lying across his lap to the other similarly crumpled bodies sitting around him in the truck.

Outside at the edge of the gate, the man in the beret twitched in the sand creating a macabre snow angel, a rope of blood spurting from his neck in a crimson arc.

Bonner turned his head, his gaze locking on the turbaned man behind him — the only one of the guards from the back of the vehicle still upright. In a purposeful flurry, the man, aided by the driver, swung the doors open and began pulling bodies from the cab like goat carcasses. Bonner caught the last flicker of life as it slipped from the eyes of one of the bodies sliding from the floor of the truck onto the sand.

The guard’s gun barrel still trailing smoke, they heaped the corpses in the dirt. Then, the driver leapt back into the back of the truck and in one smooth motion unsheathed a dagger hanging around his neck and pointed it at Bonner. His lips moved, his eyes fixed on Bonner.

Bonner stared back in confusion, not understanding why the man didn’t just speak. Again his lips moved. Bonner felt the vibrations of the car’s engine, but his ears felt blocked. He touched the side of his head and felt a trickle of warm fluid on his neck.

The driver seemed to grasp that Bonner could no longer hear. Dropping his dagger, he smashed Bonner in the side of the head with the butt of one of AK-47s from the floor of the truck. It wasn’t enough to knock him out, but he pitched forward to the floor of the vehicle between the two rows of inward-facing seats. The wide-eyed man then slapped a sandal-clad foot on his cheek to hold him down.

The car lurched into motion, vibrating through Bonner’s jaw as he lay pinned against the metal floor. He struggled at first, but each unseen turn or rut in the road contorted his body, and soon he just submitted.

After perhaps half an hour, the guard lifted his foot from Bonner’s face, but he didn’t dare move. Several hours passed, and then the truck’s engine stopped. Fresh air streamed in as the rear doors opened, and the faded light of dusk entered. Slowly, Bonner raised his head.

Behind the truck, the guard and the driver bent in unison. To his relief — odd to feel relief, he thought, in such a situation — Bonner found he could hear the murmured Arabic of their prayers. He struggled to sit up, his head throbbing where the butt of his captor’s gun had connected.

The men were turned sideways toward the vehicle, their backs facing the fading sunlight. The driver continued his prayers, but Bonner thought he saw the whites of the guard’s eyes flash toward him. Instinctively, Bonner raised his eyebrows and wanted to raise his hands, but they were tied together in front of him, so he mellowed his face as much as he could, wondering how that would translate.

Bonner watched the two men for several minutes. The terrain out the windows was dry and featureless: mile after mile of stunted thorn bushes, twists of drying vegetation and sand covered the cracked hardpan fading into the darkness. In his mind he sketched a rough circle around the capital. They had to be somewhere in the upper arc, north and perhaps west of the city. All of the clinics he worked with were in the southern finger of the country, where it was marginally wetter and aided by the short span of the Niger River severing it off from the baked desert hell that was the rest of the country. Now he cursed himself for not venturing out here in the year he had been in country. If he had, perhaps he would remember some landmark. Maybe some scrap of the country would make some sense to him.

He had forgotten his watch, which struck him as unusual. Though he had a memory for places and names, he had little concept of time. He could roam the makeshift floor of his clinics from dawn well into the darkness of early morning, or stand as still as a old carthorse over an operating table for hour after hour, and he’d swear mere minutes had passed. At the same time strained conversation at the cocktail parties with funders that his ex-wife always dragged him to on his annual trips home seemed interminable.

They’d been gone three or four hours, he figured – a clumsy guess at best, but it was all he had to go on. At sixty or so kilometers an hour, they could be hundreds of kilometers from the city if they’d been traveling in a straight line. That, he had no way of knowing. Again he was pretty sure they were above the river, which cut down by roughly a quarter the possible area where they could be, assuming the spatiality of his mental map was accurate.

He thought briefly of betraying his nonverbal plea to the guard and giving escape a shot. But to do what? Run? He wouldn’t make it 50 feet.

And the car? Not likely. Still, he peered over the driver’s seat to see if the keys were in the ignition. No luck.

In the moment he’d turned his back to his kidnappers, the car’s walls seemed to close in on him. Blankness was all he could see.

“No ideas, Doctor.” The voice came from outside the sack, and he smelled the dankness of stale grain inside, choking a bit on the dust dislodged from the bag’s sides. “No trouble,” the voice said, again in French. Bonner felt a slap on the head as if the driver wanted to make sure his command would be heeded.

The truck’s engine started. The road began to toss Bonner, unable to anticipate what was coming, as he sat on the bench. Minutes, hours and miles fell behind them, the truck quaking periodically as the driver slowed presumably to cross a rough patch in the road. The few bits of light illuminating the bag gradually dimmed until only blackness surrounded him.

To stifle his claustrophobia, Bonner began to take deeper breaths. In doing so, he sucked in more of the dust, in turn calving off the sides of the bag, and he began sneezing uncontrollably. He tried to shake the bag from his head but felt a bony grasp on his shoulder.

“S’il vous plait,” Bonner pleaded. He sneezed again. The driver said something Bonner didn’t understand.

The grip on his shoulder loosened and the guard sitting next to him in the back of the vehicle pulled the bag from his head.

Bonner shook his head to detach the dust still stuck to his skin. Outside was only darkness. Clusters of stars perforated the blackness above, but there was no moon, the characteristic nighttime glow of the desert replaced by two cones of light stretching from the truck’s front bumper. The tiny arc of the known hung pathetically in the vast oncoming nothingness.

Once he brought his sneezing under control with a few deep breaths, Bonner’s body settled. The adrenalin began to drain, leaving behind only the searing realization that he was in trouble.

Some time later, hours maybe, they arrived at a grass hut. A cloud of dust caught up to them, hanging a haze around the headlights. Bonner strained to see what or who waited for them.

To his surprise, a little girl – she looked no more than 4 years old – launched herself from a chair where she had been sitting.

“Abba!” she yelled. The guard said something in response and stepped down from the vehicle. Probably Tamashek, Bonner thought. To his ears, the syllables of the Tuareg language were halting and guttural, yet still melodic.

She met him and flung herself into his robes. He ruffled the girl’s braids, and she flung her head back and giggled. He repeated what he had said. In response, she turned her head and motioned toward the door with her chin.

The driver shut off the headlights and slid down from his seat, turning toward the back truck. His smile, half-lit by the lantern, evaporated when he met Bonner’s gaze through the window.

He opened the back door of the truck and motioned for Bonner to come toward him. Pulling a length of rope woven from palm fronds from under the ambulance’s seat, he grabbed Bonner’s elbow, guiding him to the side of the car. He wrapped the cord around the rope that bound Bonner’s hands, further tightening the makeshift shackles.

After three or four turns, he then wound the rope back on his wrists. Bonner’s fingers began to numb, and he fought the urge to struggle against the knife-like strands beginning to tear into his flesh.

The driver took Bonner’s elbow, and walked him toward the hut, and a woman emerged from behind the cloth sheet that served as a door.

She started at the sight of Bonner, reflexively grabbing the little girl whose curiosity had her inching toward him. Bonner tried to smile at her, but realized there was neither enough light where he was to be seen, nor was it likely she would be receptive.

The guard and the woman exchanged a few words. To Bonner, it was as if the guard was suddenly someone else. The icy demand from his words had melted, clearly much more comfortable in the role of husband and father, much more accommodating of the giggling girl playing among the fabric of his robes, than he ever was likely to be with a machine gun slung over his shoulder. It still hung there, the shiny well-worn wood of the rifle glinting in the dim lantern light.

He handed his wife a small pouch, and then Bonner watched as he tore his daughter from his leg in a mock display of paternal force. He tossed her into the air, the gun sliding off his shoulder and landing in the sand. The girl shrieked and laughed with the kind of joy that needed no translation.

Bonner briefly considered grabbing the gun from the ground, but the abyssal desert haunted his anticipation. And he couldn’t imagine actually wrapping his finger around the trigger, much less raising the gun toward the man’s family.

Instead he stood and watched and felt a twinge of wistfulness that his time in that way with his own children had long since passed. He thought of his kids in their own homes, unaware that he’d left the field clinic’s tight gravitational orbit to the far-off nowhere where he now stood.

As so often happened when he traveled, in his head he slipped into the scene before him. Now he was his captor, playing with his young daughter. Often, this vicarious slide would leave him with a sadness at the plight of the person he’d replaced and an appreciation of his own life.

This time, however, a certain comfort in this stolen role washed over him. He felt the warmth of the child’s body on his arm, her intent gaze on her father’s face – his face. The emotional stability that the walls of this tiny house provided would long outlast the structure itself. And there was the solidity of the woman who kept his home, whom he lay next to every night.

Back in his own skin, Bonner stood awkwardly wondering what would happen next; his captor appeared to have forgotten he was there. The driver had disappeared. When the guard’s eyes met Bonner, he stopped talking, seemingly mid-sentence. The little girl’s eyes were still fixed on her father.

As quickly as the man’s gaze had softened at the sight of his family, it sharpened like the edge of his dagger when confronted again with the presence of his prisoner.

He said something in that language Bonner didn’t understand, and then said, “Venez!” as he picked up the palm rope from the sand.

Bonner followed him away from the hut. In the darkness of the desert, the white paint of the hostage Land Cruiser picked up even the faint starlight – the only thing around standing out in a sea of nothingness and sand.

Bonner couldn’t make out the expression on the man’s dark face, but he sensed some confusion. The man held Bonner’s bound wrists and seemed to be searching for what to do next.

“What are you going to do with me?” Bonner asked in English, half trying to help him out of a situation he wasn’t prepared for.

“Shhh!” The hiss died without echo into the sand.

The captor finally settled on the truck, pushing Bonner back toward the Land Cruiser. “Where am I going to go? You don’t have to tie me up.” This time, Bonner spoke in French, and he thought the guard understood what he had said.

As his captor worked the rope around the tube-shaped running board with Bonner seated by the truck, he saw a flicker of recognition in the man’s eyes – a realization of the absurd theater of tying him up. He made a cursory search of Bonner’s pack with on hand in the darkness, and then he tossed it at Bonner’s feet.

“Thanks,” Bonner said.

His captor’s eyes searched the black horizon every few minutes for … for something. Bonner could sense the haphazard futility of the man’s actions. He was waiting for someone to come, another vehicle to arrive; that, he understood. The stolen Land Cruiser with its green diplomatic plates was too much of a liability.

Bonner would be forced into the new vehicle, something nondescript, a beat-up Corolla perhaps, or a chugging Peugeot. They would then take him over the border to Mali, where the associates of this middle man would likely have a much more organized network in the entropic vacuum left behind since a coup there had left the eastern reaches of that country a dry swamp of bad roads, bandits in a pseudo-alliance with the Islamists from north of the Sahara and overwhelmed villagers just trying to go about their lives.

So it had become a race. Surely the embassy hadn’t been empty after Bonner’s captors had killed the men at the gate. Someone would send the authorities, he thought. Marines, police, gendarmes, someone.

The shock of the attack might have taken some time to get past. Why had no American marines been at the gate? There weren’t more than a handful in the country, but had they been there, they would have followed – wouldn’t they have?

He also knew that the people who had him didn’t just call the desert home. For centuries she had shaped who they were, how they dressed and moved, what they ate and where they lived. She was an unsympathetic mother, providing little in excess. But those who survived under her watch had to be uncommonly resourceful. It was no accident that he had been brought here, no doubt a place where pursuers wouldn’t – or couldn’t – easily follow.

But Bonner still couldn’t shake the feeling that something had gone awry with his captor’s plans. Bonner had been left tied to the truck in the chilling desert night air. He worked his sweater out of his pack and slipped it around his shoulders as best he could with his tied hands.

A few moments later, the little girl came out of the hut. She moved with the jilting long stride of a child with a purpose, dragging something behind her through the sand.

It was a heavy woolen blanket – the kind Tuaregs used to pad the loads hauled by their camels. She tossed the blanket in a heap onto Bonner’s outstretched legs, and then ran back into the hut.

“Merci!” he yelled in appreciation, though it was unlikely that she spoke any French at all.

He unfolded the blanket over his legs, using his bound arms as one clumsy appendage. He realized that by simply moving around the wrap around his wrists had loosened to the point he thought he could wriggle his hands out. But then, he thought, what would be the point? He settled for the decreased discomfort the cuffs now caused him.

He settled under the rough blanket, heavy with the musk of camels and caked with the sweating salt they hauled in blocks across the world’s largest desert. It was warm, sheltering him from the chill of the night air and the un-knowableness of what was to come when day broke, and the livestock smell reminded him of his youth on a Vermont sheep farm.

As Orion arced across the sky then finally disappeared behind the truck out of Bonner’s field of vision, he slunk deeper into the cradle of the blanket. He didn’t manage more than a few minutes of sleep at a time before the chill overcame his dreams, or a desert wind from far off – the Mediterranean perhaps – kicked sand into the pockets of his ears and the corners of his closed eyes, forcing him to sit up and shake his head free of the fine grains. Each time he awoke he found newly formed trails of sand patterning the top of his blanket like the remnants of termite tunnels.

Morning did finally come. Bonner’s mouth was cracked and scratchy, dry from the night’s beating. His eyes were open and fixed on the flap of the hut as he sorted out what to do next, drifting through the early morning tiredness and trying to stave off the near-freezing morning chill. He had just tucked his head back under the blanket and ground his forehead into a pillow of sand when he heard the low murmur of voices and then the slapping of the fabric door.

He moved the blanket off his head with his chin and peered in the direction of the hut. His captor carried two bowls and set next to Bonner. One had clear water with a few grains of sand shifting back and forth at the bottom of the bowl. The other had a few handfuls of millet paste, presumably from the previous night’s dinner.

“Thank you,” Bonner rasped, draining the water bowl.

His captor didn’t make eye contact, his face pinched as though trying to puzzle something out, continuing to scan the surroundings.

Bonner followed his eyes to the horizon but saw nothing. The man said a few words, hushed and under his breath, that Bonner took for something neither he nor anyone else should hear, even if he could understand what had been said.

Then the little girl, who had brought him the blanket the night before, came out from under the door, dragging a sword nearly as long as she was tall. The weapon was straight and sheathed, the flourished hilt leaving wide snake-like trails in the sand.

She lifted her hand toward her father, offering the thread of a strap that ran from one end of the sheath to the other. Reflexively, Bonner drew up his legs in a jolting full-body jerk. The little girl started and then began to wail with heaving sobs, clinging to the folded fabric around her father’s legs. Her crying came in waves — a few revving inhales, followed by a cathartic scream.

Bonner eyed the sword as it came out of its keeper. The girl’s crying had faded to soft irregular whimpers.

Was this really it? he thought. The situation didn’t make any sense. Why bring him food, only to dispatch him moments later, before he’d had a chance to even touch it?

Sure enough, the man hacked through the rope attached to the car, then sawed through the cuffs of cord holding Bonner’s hands together.

“So this is where we’re at,” Bonner said, searching for any hint of comprehension on his captor’s face. Again, Bonner scanned the landscape as he stood up, rubbing his chaffed wrists and then grabbing his backpack. All of the empty expanse dotted with the odd sprig of dry grass or acacia, formed the infinite, invisible walls of his prison. He also felt the burden this placed on his captor, to be warden of this expanse.

His captor grabbed his wrists, said something to the little girl and guided Bonner into the hut. The girl followed, bringing with her the food and now-empty water bowl.

The captor sat down next to a woman who held a suckling infant in her arms. She was shirtless, unfazed by the stranger entering her home. A dark nipple peeked out from behind the baby’s body.

Bonner sat down cross-legged. His captor pushed the food bowl in his direction, said something and mimed taking food in his hand and placing it in his mouth.

Bonner reached out and took a handful of the cold paste, dipped it into the congealed sauce that had taken the shape of the bready mass and scooped it into his mouth.

Few meals in his life satisfied his hunger like that bowl of millet paste and sauce – tuwo, they called it throughout the country. He’d politely worked his way through a few bowlfuls in the past when friends from the hospital invited him for dinner, but it had always been out of respect for his hosts rather than a genuine affinity for the stuff.

This time, though, Bonner didn’t look up until he’d cleaned the last bit of sauce from the side of the bowl with his finger. As he wiped his mouth with the sleeve of his shirt, he noticed that the man had set to work pounding a piece of metal with a hammer – a piece of jewelry perhaps – and the woman and the little girl sat smiling at each other, cocooned in their own quiet conversation.

Bonner tried a smile when the little girl looked at him, and she let out a chortle. Children had a sixth sense for tension, and her father’s shift, this invitation into his home, must have made her feel better. He felt the same way.

He reached into his pack and pulled out his bucket. Opening the leather wallet, he slipped out a worn and creased picture of his daughter when she had been about the girl’s age. He held it out, and he imagined her little brain weighing curiosity against apprehension.

Her curiosity won out: She approached Bonner and took the picture in her hands, bringing it close to her face to study it and then looking back at Bonner’s face. They both smiled.

His captor pounded away at the strip of silver, occasionally slipping it into a small pile of ashy coals, which he would blow on until they glowed red and then he’d pull the red-hot metal from the pile. A tiny blue teapot also sat on the coals. The boiling liquid bubbled out and down the sides of the pot, a faint ‘rat-tat-tat’ sounding as it lifted up the teapot’s lid and it slammed back down again in quick succession, drawing Bonner’s attention whenever his captor’s pounding ceased.

He had flattened the chunk of metal to the length and thickness of a stick of gum, occasionally starting from high above his head when the meat of the silver strip was squarely on the metal post embedded in the sand.

Finally, he paused, reached behind him and grabbed a plastic bag full of white sugar. He tipped the bag up and poured some of the coarse granules into the pot. He picked up the pot and swirled it around in the air two or three times before setting it back on the coals, and then slapping his loose-jointed fingers together in the air, presumably due to the heat.

After a few minutes and more pounding on the silver leaf, he picked up the teapot. Starting low and raising it high above his head, he splashed some of the liquid into a shot-sized glass and then poured it back into the pot. Repeating this perhaps two dozen times, he finally took a small sip of the greenish liquid.

Satisfied the tea had boiled long enough and was sweet enough, he dumped the remaining liquid from the glass back into the teapot. Then, with a flourish, he filled the glass until the foamy head just breached the top. He held the glass up, turning it in his hand as if to admire his artistry and then extending his arm to Bonner.

Perplexed by this offer of the first glass – a sign of honor, of respect – Bonner reached out and took it. He took quick sips as he had been taught by his friends at the clinic, letting the tight-knit foam trap the stems and flecks of tea leaves that had made it through the teapot’s strainer. He welcomed the warmth, in such small measure though it was, after the cold night’s sleep.

Bonner handed the cup back to his captor, who held the teapot, ready to pour his own glass. Then he poured one for his wife. Then he dolloped a splash of liquid into the empty glass and let the little girl have her sip.

He had poured some water back into the pot and started measuring sugar in the glass when he looked up abruptly toward the door. His hand remained in position, white sugar spilling over the sides of the glass and mingling with the beige sand on the floor of the hut.

Then Bonner heard it too. Both men jumped toward the door at the same time, but the nimble Tuareg beat Bonner there, tossing him to the ground with an uncommon show of strength for his size. The sound of a vehicle’s engine was louder now, straining over the last few ruddy potholes in the road.

Bonner’s captor pushed the door open, and there was a burst, like cracking wood, followed by a thump just outside the wall of the hut. Bonner was still on the ground after the man had pushed him down.

Bonner crawled to the door, lifted the corner of the flap and saw his captor’s body lying contorted on the sand. Bonner couldn’t see the man’s face but he didn’t need to – he was too familiar with that sort of stillness. Ducking his head back inside, his eyes straining to adjust back to the dimness again, he looked at the woman and her child. A vehicle’s diesel engine roared to within what sounded like a few feet of the hut. Then it cut off.

“Allo?” Bonner yelled. His voice cracked, and he wasn’t sure whether to speak in French or English or try one of the few phrases he knew in Tamashek. “Who are you?” he yelled, making a snap decision, thinking that if it was a rescue team and they heard English, they wouldn’t blindly fire into the hut. If it was his captor’s compatriots, they would know he was there anyway, so it wouldn’t matter what language he chose. With them, he figured, he was probably already dead anyway.

He heard yells and murmuring in French, though with the lighter lilt of the French taught in Europe. He yelled again, this time in French, identifying himself as a doctor from the Catholic mission.

“Doctor,” a voice said in accented English. “Please come out. You have no weapons, yes?”

“No, none.” He motioned to the woman to stay put. Her face was frozen in a look of horror that said she understood nothing of what was going on.

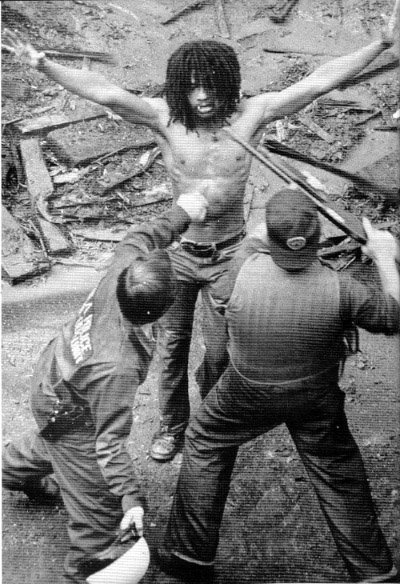

Bonner pushed the flap of the hut back slowly, extending his empty hands out in front of him as he crawled, balanced on his knees but hunched over.

The French soldiers grabbed his wrists, dragging him free of the hut. They lifted him to his feet and motioned toward the hut.

“Are there others?” the one who seemed to be in charge asked in English.

“Yes, but…” Bonner replied. He hadn’t finished, but the three soldiers had already turned back toward the hut, and the leader gave a flick of his head toward it. The other two sprayed the woven mat hut with gunfire from their machine guns.

“No!” Bonner instinctively moved back toward the hut, and the soldier in charged yelled for the guns to stop. “There’s a young girl in there!” Bonner said, as if his explanation could reverse what had just happened, as if his protests could bridge the tiny gap that now stood between a fragile life and infinite death. “What did you do?” Bonner had fallen to his knees.

“This is the last of the kidnappers, Doctor,” said the man in charge, who stood apart from the other men. Smoke trailed from the barrels of their guns. “We caught the others last night. They told us where you were.”

“Why the hell is the French army here?” Bonner said, staring at the flag on the soldier’s sleeve.

“They can tell you more in Niamey this afternoon, Doctor.”

The soldier in charge then instructed his subordinates to remove the bodies – la femme et sa petite fille – from the hut.

“You knew they were in there?” Bonner demanded, leaning toward the one in charge.

“It is regrettable, but it could not be helped,” the soldier explained. “We cannot have her growing up to hate us … or you.”

“Are the other kidnappers dead too?” Bonner asked. The soldier in command just looked back at him, saying nothing.

Bonner stood dumbstruck as the bodies were carried out – the woman by two men, just one returning to retrieve the girl – and laid in a neat row next to Bonner’s captor. The woman’s face was bloody, apparently from a series of bullets that had shredded her windpipe and jugular. The girl however lay peacefully, as if she was just sleeping, a tiny red hole in her tattered dress sat just below her heart. Her tiny hand still held the tattered photograph of Bonner’s daughter.

He walked over to the bodies, ignoring calls from the commander to leave them where they lay. He dropped to his knees and felt for a pulse, first on the child’s neck, then by placing a hand on her chest. The warmth of the body struck hope in him, but nothing inside the tiny body reverberated against his fingers.

“Doctor, these are bad people,” the commander said, pulling him up. The other two soldiers had picked up the blanket from where Bonner had spent the night and spread it over the corpses. How small the contour of her body was, a half-person, an afterthought, next to her parents.

“You must understand,” the commander said. “We had no choice.”

“Yeah?” Bonner said. Then he pointed at the shape of the man’s body under the blanket. “I kind of get the feeling that’s how he felt too.”

* * * * THE END * * * *

Copyright John C. Cannon 2014