Tryouts by Brodie Lowe

Tryouts by Brodie Lowe

Overgrown hedges of hawthorn lined the rusted fence, interlocking one another, bunched together like rows of men in broad-shouldered jackets looking inquisitively outward on the rest of the world in a mixture of confusion and ill-tamed constraint. They encapsulated an unassuming cottage which was quickly losing its battle with gravity; the top of the front doorframe sagged in a slight frown and the single thatch roof bore several misshapen divots like those in an uneven hill of snow whose ground had been trampled on by far too many heavy-footed hikers. If the front of the abode had been a human face with consciousness, it would have looked back at visitors with a reluctant visage that seemed to say “Oh, another one of you. Go ahead, if you must. Come in, if you need to. But don’t shut the door too hard. Quietly tread on my floor. You see, I am in much pain. I’ll have it looked at soon enough, that is, if I can get up for a day and move around.” It wasn’t welcoming in the least, but its owner who presently dug in the front yard, back hunched and rounded like a turtle’s shell, was an intuitive, noble gentleman of just over seventy years. And he was filled with a certain type of determination that only comes on Saturday mornings after having overslept, refreshed and rejuvenated.

The shovel hit a root hard, sending pain up the old man’s arm until his atrophied shoulder tremored in response. He turned the spade and dug deeper, muttering “I know you’re here. Seen your momma around these parts not too long ago.” His dull eyes searched frantically for any semblance of white beneath the black soil. There had been a snake rummaging about beneath the undercarriage of the wild blackberry bushes nestled under the windowsill. He scuttled to the right and traveled closer to the house, the top of his head grazing the bushes’ thorns, digging like a madman until his entire torso was covered by foliage. Soil launched through the air, over his back, running into the waist of his pants as he dug like a canine retrieving a buried bone. Then he saw it, or them, rather: fifteen tiny snake eggs, soft to the touch, glistening in what little sunlight broke through the vegetation. He raised his shovel to bring down a rain of death and terror on the little cads, taking careful aim, until a slow, squeaking sound came from the corroded fence. He paused and turned around to face the noise.

His new guest – a boy, ten years of age, whose baseball cap was two sizes too big and St. Louis Cardinals jersey fit him like a bathrobe, the team’s logo as big as a catcher’s mitt – entered the decaying premises. It was his grandson. The old man had bought the jersey for the kid last Christmas, knowing that it would be too big, but also recognizing that in doing so, it fit the old man’s budget quite nicely, a gift that would keep on giving until, that is, the boy outgrew it or switched up on his favorite team. His bloodline did have a traitor in it, a recent revelation.

“Great. Just in time. Come over here. Take a look,” the grandfather said, waving Drew over. The boy shrugged his backpack, readjusting it around both shoulders (it was heavier than usual, having been stuffed with baseballs and gloves and a few extra comic books to boot).

Drew’s parents didn’t necessarily get along with his grandfather – a development that started three months ago. There was a money issue, a common fissure that came between familial relationships. Someone (Drew’s father) had sold a business and its property outright, taking all the profits, even though there had been a verbal agreement to split it down the middle. Words were said, but then again, “words didn’t amount to a hill of beans,” as Drew’s grandfather, Theo, had said. “I started the damn thing. Worked my ass off all those years for it, too.” But ten-year-old Drew didn’t get caught up in it – partly because he was too caught up in Adam Wainwright’s phenomenal abilities on the mound, but mostly because he was too young to understand any of it. Money bought baseball tickets and hotdogs and soda. And Drew still had those things in life. So it didn’t affect him at all. Nevertheless, Drew’s parents had dropped their son off at the crooked mailbox at the top of the mile long dirt road that led to his grandfather’s cottage as it was that time of the year – that one week out of the summer, in between schoolyears (fourth and fifth, in Drew’s current case), when Drew was allowed to visit his remote grandfather.

Drew had walked the whole way down that road. But he was fine with it. After all, meeting a living legend was an aspiration of all his classmates. Theo Green was known throughout sports buff circles as “The Alcatraz.” Not because he resembled one, no; in fact, he looked more like a hand-me-down version of actor John Garfield. The intensity and good looks were there, but the smile wasn’t; his right incisor had been knocked out thanks to a line drive from the batter’s box that one time he played shortstop. He never attempted to get it fixed – a reflection that could be seen on the deterioration of the residence. He had been a professional baseball, an outfielder, from the time he was twenty to thirty-three. He could nearly jump over the back fence as he caught balls that were sure to be homeruns, thanks to his longer than normal limbs. Hence the nickname.

Drew considered it an honor to be around him. To learn baseball tips, tricks, lingo, and hints from the fount of knowledge that flowed from Theo’s head. To visit Theo’s old stomping grounds and hear behind-the-scenes stories of his fellow teammates whose faces Drew could place with the names (thanks to a sprawling collection of vintage baseball cards) was a dream come true.

“See those guys down there?” Theo asked pointing a finger to the grave of eggs he had unearthed.

“Snakes.”

“How’d you know?”

“Nat Geo.”

“Who’s Nat?”

“National Geographic channel.”

“Still get those mags mailed here. Didn’t know they had their own channel now,” Theo replied.

“You’d be surprised what’s on television nowadays, Grandpa.”

“I’m sure I would. They show you how to…dispose of ‘em?”

“You’re supposed to eat them. Scrambled with salsa.”

“Wise guy.”

“Did you know that addrs can’t subtract?”

“Hardy-har.”

“They eat rats, don’t they? Aren’t they good for something? That’s what Nat Geo said.”

“They can be, but I’ve got this guy over here to look after,” Theo said, motioning his head toward the front window, a Yorkie perched on the back of the couch peering out at the two, tail wagging. “Cubbie,” he said. The dog’s ears perked up at the sound of its name and its tail gained speed.

“Right,” Drew said.

Theo’s decision to completely annihilate the venomous bombs of anarchy changed. “Maybe we can come back later and take ‘em someplace else.” Then he noticed how red Drew’s face had become. “You thirsty?”

“Parched.”

“Long walk?”

“Doesn’t bother me. Helps me get ready for the upcoming season.”

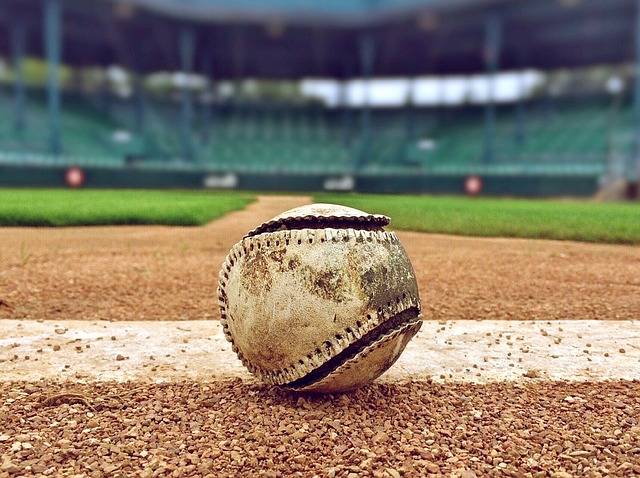

The two entered the air-conditioned cottage, Drew greeted an ecstatic Cubbie, and they sat down with a pitcher of sweet iced tea and two tall glasses filled halfway with giant ice cubes. Theo gingerly poured the pitcher into the glasses and sat at the dining room table next to Drew. After downing nearly half of his glass, Drew unzipped his backpack. “Got a new one,” he said reaching in and revealing a new baseball, the words OFFICIAL SIZE OF THE MAJOR LEAGUE written across its curvature. With enough hitting and abuse, the ink would smear, but the weightiness of its legitimacy wouldn’t fade. He was proud to have such a baseball formerly endorsed by the majors. “And this,” he said revealing a black Rawlings Elite series glove. He handed it to Theo.

“This one’s long enough for a first baseman. About thirteen inches,” Theo said, and then looked quizzically at Drew. “You thinking of switchin’ positions?”

“Outfielders need to have hops. I don’t have any. I’ve got a little. But not much. Just enough for first base. And from what I can see out there in the field, that’s where most of the action is.”

“So, it’s official? You trying out, or have you already got the position?”

“Got tryouts at the beginning of the next season. I’ll have to beat out Jeffrey Langlier. He’s the starter. A grade ahead of me. It’ll take a lot to beat him, but…”

“You wanted to get some work in while you’re here. Practice a little, right?”

“That’s what I was going to ask you about,” Drew said underhand tossing the ball to his grandfather. “Thought that you could help me. Give me some pointers. We’ve got all week to drill. You’re, uh…what’s that word that means well-rounded?”

“Versatile?”

“That’s it.”

“I wouldn’t say that’s a good word to describe me.”

“You’ve been around long enough. Longer than most. Long enough to help me up my game.”

Theo rubbed his thumb across the red stitches on the new baseball, mulling a distant memory over in his head of an iconic play from long ago. “Tryouts, eh?”

“Yeah. The thing about those is that it’s no luck of the draw. You either have it or you don’t. And I gotta get there. To that point where I can have a fighting chance.”

“Unless the coach is the kid’s dad,” Theo muttered under his breath, quickly running his words together, as if he had dealt with such politics before. “Then you might be up against somethin’ more.”

“What?” Drew was still too young to understand how insurmountable small town politics could be. Especially those where the parents controlled the strings. “Jeffrey’s dad is the coach, if that’s what you mean.”

“Is he as good as you?”

“You asking in general?”

“Generally.”

“Comes close. But I’m better. Got more hustle and stamina. Got a better batting average than him. I can throw further, too.”

Theo turned his attention to the glove in his hand; its fresh leather smell wafted through the air. “This thing’s hard as a rock,” Theo said, pressing his hands into it, folding it like hardened beef jerky. “Got an idea. I’ll be right back.”

Theo hurried to the damp garage. He snagged an old bottle of glove oil spray. The nozzle was crusted over, but the oil inside was still liquid and he tested it out, swishing it around in the bottle. About a quarter full. That would be enough. If the nozzle refused to work, he’d just dump it out onto the glove in a pool of sludge to loosen up the leather.

A black snake slithered across the cold concrete slab upon which the garage rested. It sounded large as it bumped into the empty tin can that used to hold gasoline for Theo’s now out-of-service lawnmower.

For the next three days, the two of them threw baseball, stopped grounders, caught pop-ups, and drilled relays. By Wednesday, Drew felt like his skill had slightly increased, but he wasn’t sure if it was in his head or really a result of hard work. That afternoon, the two of them sat down in the living room to a meal of meatloaf and mashed potatoes.

“It’ll help you recover,” Theo said. “’S what I used to do. Made me stronger.”

They downed the meal while watching The Stratton Story. Throughout the viewing, Drew thought that Jimmy Stewart’s character of determination was a reflection of his grandfather – a no-nonsense type of guy with an unrivaled work ethic. Throughout the movie, Theo didn’t seem much interested as he read from a navy blue book whose title read Agnes. Soon, Theo fell asleep on the couch, the opened book resting face down on his stomach. After the credits began rolling, Drew turned off the television set and went to bed.

Around midnight, Drew awoke in a cold sweat. He didn’t know what had startled him, but it wasn’t a soft awakening. It was quick and sudden and he wondered if a loud thud had broken through his dreams. But whatever the sound was, it didn’t repeat itself. He stood from the bed and made his way into the kitchen to grab a glass of water; the three days of intense baseball drills had left him dehydrated.

Standing in the yellow light pouring from the open refrigerator, chugging water from a grimy Nestle bottle (he had dropped it in the dirt when Theo surprised him with a grounder, yelling “Always be alert!”), Drew noticed his grandfather still asleep on the couch. The book he had been reading during the movie was crumpled on the floor beside him, a few pages folded messily underneath.

Must’ve slid off his lap, Drew thought to himself. The book’s title, Agnes, embossed in gold lettering, glared back at Drew. The letters themselves seemed to squint at him. He could’ve sworn that his eyes started burning, and it reminded him of the light reflected from the sun, through his magnifying glass, that he had used to burn ants earlier that summer. Now, he felt like one of those ants. The heat spread from his eyelids to his cheeks and down his neck. He looked away. Then he looked back, the book drawing his interest.

Drew slowly walked over to the tome; it looked thicker than before and seemed to be pulsating. He pinched it by the spine with both hands, picking it up; it felt heavy like a wet mop. He hoisted the monstrosity to the kitchen table, using the refrigerator’s light – the door still ajar – for reading purposes.

Drew flipped to the first page of the hardback volume (one that qualified for being in an encyclopedia section at the library, one that was hardly ever referenced because of its enormity) and read its first words: AGNES GREEN 1942 – 2014.

Agnes Green. Drew knew the last name. It was Theo’s; it was Drew’s father’s; it was Drew’s very own. A family name. But he had never heard of Agnes. He turned the page.

The book went on in great detail about the birth of Agnes, Agnes’ childhood in the 40’s and 50’s, and subsequent fascination with Elvis Presley during his rapid rise throughout her teenage years. It spoke of her meeting a young baseball player by the name of Theo Green in her twenties.

It was a biography which was told in an omniscient voice – one who knew Agne’s deepest thoughts, darkest secrets, brightest hopes, and most desperate of prayers. It was more than a journal.

“What are you doing?” Theo’s voice came from behind Drew.

Drew turned around, startled, goosebumps forming on the back of his neck. His haggard grandfather stood in a trance, a look of disapproval on his face. “What is this?” Drew asked to clear the air.

“How far are you into it?”

“Not too far. Who wrote this?”

“Agnes. My wife.”

“Her journal?” Drew asked, but he knew better. Journals weren’t written like this. They were more streams of consciousness. Told in the first person. There were shorter entries in those. They didn’t have chapters like this one.

“Sort of. Her thoughts…”

Something hard fell in the basement with a loud thud. Theo’s head swiveled toward the basement’s door at breakneck speed. “I’ll be right back,” he said. He took the book from Drew and tossed it on the couch. “Leave it alone. It’s sentimental.”

Drew sat motionless, a block of ice. Theo disappeared down the dark staircase that led into the basement. Seconds later he emerged with another tome – one about equal in length. He closed the refrigerator door, turned on the kitchen light, perched his eyeglasses atop his nose and read the title aloud. “Theodore.” He paused, looking intently at the front cover, his heart beating so hard in his chest, that Drew could hear it. He opened the book, muttering under his breath “A different one.”

“What’s going on?” Drew asked.

“Nothing. We got too much sun today. ‘S the reason why we’re so restless tonight.” The last word drew out of Theo’s mouth like a slow locomotive. He took the book to the top of the basement’s stairs and lingered in the doorway before turning back to address Drew. “Better get to bed. We’re hittin’ the batting cages tomorrow.”

THE NEXT MORNING, Theo handed rubbery pancakes, the edges burnt black, to Drew on a plate. While pouring a pitcher of syrup over the mountain of charcoaled pancakes, Drew took in Theo’s dazed eyes. The syrup flowed like whitewater rapids onto Drew’s plate, drenching it; so much syrup had been poured that the cakes began swimming in the amber liquid.

They entered town in Theo’s beat up 1963 Ford Thunderbird, hard mold blending in with its forest green paint. Theo stopped for gasoline (he hardly ever used the clunker), as it was almost on empty, and picked up the day’s newspaper. When they visited the batting cages in town, Theo sat cross-legged on a bench just outside the fenced-in area, a worried look strewn across his face as his eyes frantically scanned the newspaper. He shook his head in dismay.

After the pitching machine ran out of balls to hit, Drew took a break and took a swig of water next to his grandfather. Theo stared off into the distance, out of the nearby window into the cloudless blue sky. Now, the newspaper was on the ground, abandoned by Theo, opened to the obituary section.

Soon, it was Friday. Saturday morning would mark the end of Drew’s trip. What had started out as a fun, learning summer week with his grandfather had slowly descended to one of subdued gloom, the mood so somber, a guest would suspect that there had been a death in the house.

Theo and Drew watched It Happens Every Spring, a story where a professor discovers a chemical that causes baseballs to avoid all wooden surfaces, on Theo’s old eighteen inch Magnavox television set. As usual, Theo fell asleep before the movie was over, but tonight, the book entitled Agnes was nowhere to be seen.

Then Drew heard it. A loud thud in the basement. Almost identical in sound as the clatter on Wednesday night. There was no bounce, just a sickening slap. Drew rose from the couch, the television’s light flickering like lightening across the living room.

Drew slowly turned the basement’s knob so as not to disturb the noise-maker downstairs. He couldn’t tell if it was someone who caused the clamor, something that was not human, or what. He turned on the switch at the top of the stairs, but it only shone enough light for him to plant his footing on each step of rotted wood. From his vantage point, he could see the long, narrow stairway below and the concrete floor. The rest after was darkness.

Once he reached the bottom of the stairs, he spotted another switch that he then turned on; although it took more effort than expected (the switch seemed to be magnetized to the plate whose screws were rusted over). Fluorescent lights overhead, in between the wooden joists, enshrouded in ill-placed insulation, clicked and shuttered to life; moths and entrapped bugs flapped their wings (it reminded him of noises made from shaking a glass jug half-full of light-as-a-feather popcorn) in the lights’ plastic encasings.

After several long seconds of blinking lights that would’ve made an epileptic close his eyes, the room’s perimeter became clear to Drew. The walls – all of them – were lined with bookshelves as tall as the ceiling. Each shelf had books packed tightly beside one another like sardines in a can, all different sizes in thickness and length. There must’ve been thousands of them. They were all the same color – the same as the Agnes book. Their binding looked leathery, as if they were all covered in dried-up skin of some sort. However, there was one that was grievously out of place, right in the center of the room, resting on the cold concrete floor, facedown. Drew realized that he was standing over it in a slight trance, about to pick it up.

“I read ‘em when I know the person,” a voice broke through Drew’s thoughts. Drew turned around to see Theo, looking at the shelves with both adoration and hesitancy. “Except when I don’t. Can’t connect with ‘em. Unless it’s someone a little important, that is. Like one in the public eye. What the public doesn’t know, I can be enlightened on. What that person’s motivations were during their life.”

“What’r you talkin’ about?” Drew’s southern twang betrayed his origins in his voice. It always did that when he got nervous. When he got older, however, it would come out when he’d be either nervous or drunk. Or angry. Or all three.

“Each book is a life.”

“Like grandma’s?”

“Like her book, yes.”

“Except they aren’t journals, are they?”

A sizzling noise started above their heads, sounding like sausage on the stove. Drew assumed it was one of the ceiling lights dying. “Nope,” Theo said, his eyes rising to the ceiling, to one spot that wasn’t dressed in pink cotton candy, one spot that exposed only naked wood. “Another one’s on its way. Better step back,” he said calmly.

The sizzling grew louder directly above Drew’s head. Something navy blue poked through the ceiling as the wood peeled back like ash, glowing bright red around its curving, folding edges. It was another book falling through the opening above. The wood opened all the way, revealing the rest of the book, until it let go and fell. Drew skittered out of the way.

“When we – me and your grandma – bought this place, we were shocked at first. Like you are now. But somethin’ about this basement…some sort of portal…allowed us both the benefit and nightmarish anticipation of knowin’ when someone was about to die. Usually it’s within twenty-four hours. Sometimes, it takes damn near a week for the person to kick the bucket. Once those upstairs deem it necessary for that person to pass on, that is.”

“You can’t be telling the truth,” Drew said. But he had just seen the ceiling open up, drop a book on the floor and close back as good as new, without a blemish.

“It’s why I never moved. Became an addiction. Knowing that I could be next. But never knowing when that jackpot would hit. Like playing the lottery. ‘Cept one you don’t want to win.”

Drew picked up the book that had just fallen. He turned it over in his hand. It read: RICHARD. He opened it to the first page to see the full name. “Coach Cooper? It’s… it’s my coach,” Drew said, his breath catching in his throat. He flipped through the pages. “It’s…it’s talking about his son, Jeffrey…when he was born.” He flipped to the last page. Worry drenched Drew’s voice.

Theo smirked. “Well, I’ll be damned. Evens out the playing field a little, wouldn’t ya say?”

THE END

Copyright Brodie Lowe 2019