Leverage by Paul Edmonds

Leverage by Paul Edmonds

Mort Peters’ office was located above a scuzzy nail salon stuffed with a platoon of emaciated Asian women who looked like recent liberations from a sex-trafficking ring. The shop’s fluorescent lights threw a garish glow onto the sidewalk. Ben stood inside the bright rectangle, double-checking the address he’d scribbled onto a scrap of paper. It was a match.

He was already an hour late, but he stood there a moment longer, watching the women scuttle about inside. They commiserated behind the dirty glass, their faces drawn down into unhappy expressions, fractures of their alien tongue escaping through an open window and joining the steady din of car horns and rumbling city buses.

Ben adjusted his tie, flattened the front of his coat, and then stepped through the large double doors leading to the building’s upper floors.

The stairwell had a tenement feel, familiar to Ben from his seventeen years in the grimy, trash-strewn bowels of Pittsburgh’s public housing system. The rickety stairs shifted and popped under his feet, and the poor lighting conjured in his mind images of shadowy drug deals and squatting bums.

The doors lining the fifth floor hallway offered entry to several concerns of questionable status. Most of the rooms behind the frosted windows were dark and silent, and several of the neglected enterprises were approached by undisturbed drifts of dirt and dust.

Ben walked to the end of the hall and hesitated with his hand on the chipped brass doorknob of Suite 5J. The lettering on the glass had peeled away, leaving behind a faint image of the suite number and the words “Peters Talent Inc.”

He rested his forehead against the glass and weighed his options: music or the army. His mother had campaigned for the army, said the monthly allotment he’d send home would keep her and his four sisters off the dole. But he’d made an impassioned argument for his future as a singer, and his mother reluctantly granted him a six-month reprieve.

He’d made several inquiries and discovered that agents were resistant—if not outright hostile—toward the idea of touching unsolicited talent. Turns out field scouts did most of the work, scouring street corners and churches and rec centers in the black neighborhoods, hoping to find the next version of the Coasters or Little Richard. Ben was about to resign himself to Fort Benning when he came across a small classified ad in the back of a local music magazine called Pop Makers. The sparse copy stated that Peters Talent Inc. was on the lookout for young Negro singers. He called and was patched through to a man named Mort Peters.

Peters had Ben sing a Drifters tune—“There Goes My Baby”—over the phone, then ran him through a perfunctory series of questions about singing experience and preferred musical styles. Ben was elated when Peters said he’d meet with him, if he could find his way to Philadelphia.

Ben couldn’t ask is mother for bus fare—not after her speech about financial duty—so he sold his only possession of monetary value: a transistor radio he’d built with his father from an expensive Sears and Roebuck kit. It’d been his tenth birthday present, a rare treat his dad had saved for. He took it down to one of the local pawn joints and handed it over for fifteen dollars, just enough for a round-trip bus ticket to Philly and a dry-cleaning of his only suit.

Now here he was. All jitters and second thoughts. It was the building mostly, a dispiriting tomb of soggy plaster and bare light bulbs and failed businesses. His internal flags had been raised, told him to run to the bus station and hightail it back home.

Then he thought of the radio, one of the few souvenirs of his father, sitting in the front window of that hock emporium.

He took a deep breath and stepped inside.

The reception area was deserted. He walked to the center of the room. A tiny bathroom stood to his left, empty except for a cracked toilet and a bare space on the wall where a sink had once been. To his right was an old metal desk. Spread over the top were several dog-eared fashion magazines and a couple ashtrays choked with butts kissed by red lipstick. Behind the desk was a closed, unmarked door.

Ben looked up and saw dozens of framed photos hanging from the walls. Rows of familiar faces smiled down at him. Ray Charles and the Miracles and the Five Satins. Black singers who’d found fame and fortune onstage. His apprehension began to recede, and a sudden rush of simple optimism assumed the vacated space.

He went to the closed door and tapped it with the tips of his fingers. A clatter of chains and shifting hardware communicated through the hollow wood. The door swung open.

A short, portly man stood inside the office, his smile crooked, his thin hair slicked back and glistening with smelly tonic. He wore dainty wire eyeglass frames imbued with amazingly thick lenses. A dull, baggy suit hung from his stout body, accentuating his unappealing proportions.

He extended a chubby hand. “Mort Peters,” he said, and looked Ben up and down. “And you’re Benny.”

“Yes, sir,” Ben said, and slipped his hand into Mort’s. “Sorry I’m late. I took a wrong turn at—“

“No worries,” Mort said. “No worries at all. Come in, let’s talk.”

Ben stepped forward, taking in the cluttered office. A large desk stood at the far end, its surface lost underneath a mess of folders and unopened mail. A bank of filing cabinets stood behind it, most of the drawers hanging loose and crooked. Next to the cabinets was a door with a 1960 calendar tacked to it—a cheap giveaway from some place called Squiggly’s Auto Body. Stacks of reel-to-reel tapes stretched to the ceiling along both side walls, curls of tapes hanging down from some of the open boxes like diseased vines.

Then he caught his first glimpse of the long leather sofa set against the back wall. An Asian girl was stretched out on it, wrapped in a tattered Indian-style throw. The blanket was pulled up to her chin. One of her small feet poked out from underneath the mangy fabric, toes twitching furiously.

“She won’t bother us,” Mort said, ushering Ben toward a small wooden chair in front of the desk. “She belongs to one of the ladies downstairs. Sit, sit.”

Ben sat, and Mort took a seat in a large high-back chair behind the desk.

Mort cleared a space and rested his hands on a coffee-stained desk blotter. He fingered a long gold-plated letter opener that had been hiding under the shifted clutter. “So, you want to be a singer? Yes?”

Ben turned to get another look at the girl. Drool ran from the corner of her mouth. Her eyelids fluttered rapidly, as if hooked up to a loop of electrical pulses.

He turned back around, a million dark premonitions congregating in his mind.

“Yes, sir,” he said, his voice cracking. He coughed into his hand. “Yes, a singer. Very much so. I’ve always—“

“And famous, too? Perhaps even rich?”

Ben forced a smile. “Yes, Mr. Peters. That’d be real fine.”

“Well then, Benny, we’re a match made in heaven. I can make those things happen for you.”

Ben’s smile faded. “That sounds great, Mr. Peters. But I thought the music business was hard to get into. I mean, that’s what all those other fellas told me, the ones I called up…well, before we talked. They said selling records and making it big is a one in a million shot.”

Mort laughed heartily and leaned back in his chair. “You’re wonderful, Benny, just wonderful. If you take away nothing else from our meeting today, remember this: in life—and in this business especially—it’s all about connections. Who you know, who owes you favors. Success isn’t about luck—it’s not the goddam lottery. It’s not even about talent, when you really break it down. It’s about having the right person in your corner.”

Ben shifted in his chair and fondled the plastic buttons on his suit coat. “Sure, Mr. Peters. I hear you. I wasn’t trying to tell you your business.”

A loud moan echoed through the room. Ben turned around and saw that the girl had shifted. The blanket had fallen slightly, exposing the side of a bare breast that was really no more than a tiny nub.

Ben’s hands began to tingle, and his mouth went as dry as laundry lint.

Mort rapped on the side of the desk. The sound broke Ben’s daze, and he whipped back around.

“Pay attention, Benny, because I’m the man with the plan.” He went into the top drawer of his desk and came up with an index card. “I hold in my hand the name and number of a very influential person. A giant in the business. One call and he can have you in the recording studio next week, with top-notch songwriters and crackerjack studio musicians to boot. Just one call, Benny. How does that sound?”

Ben swallowed, and for a moment his breath caught in his throat. He could feel sweat trailing down his back and into the crack of his ass. He took another tentative look over his shoulder and saw the girl staring back at him with drowsy, squinted eyes.

“That sounds fine, sir. But…but my daddy always told me to look out for things that seem too easy—too good. Said there’s usually a catch.” He looked at Mort desperately. “Is there a catch, Mr. Peters?”

“Boy, there’s always a catch. The ongoing fee for my assistance in seventy-five percent.”

“Seventy-five percent of what?”

“Of everything you make. For every dollar this business pays you, you will give me seventy-five cents.”

Ben loosened his tie. “Not to sound ungrateful, Mr. Peters, but that strikes me as a pretty big piece.”

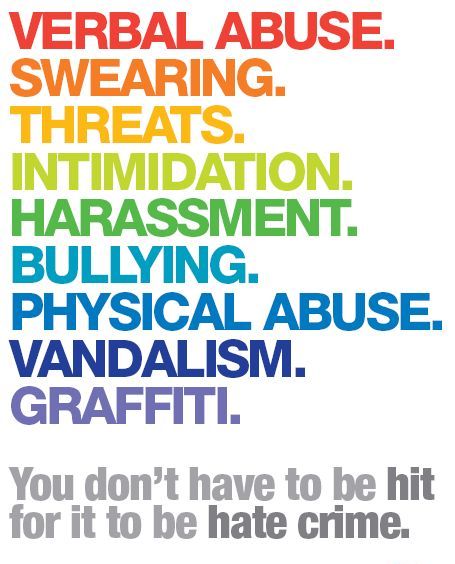

“It is a big piece. But what’s your alternative? A lifetime of hard, unsteady employment back home? Watching your mother and sisters scrimp and scrounge to survive? Or maybe prison. I hear a lot of you colored boys turn to crime when times get tough. And believe me, Benny, they’ll get tough. Tougher than you can imagine.”

Ben squirmed and pulled at a loose thread on his pants. He looked down and saw that the stitching had come unraveled. A wink of dark skin was visible through a small rent in the thin fabric. The suit was cheap, a bargain basement deal he’d picked up the year before to attend his father’s funeral. It felt awkward on him now, the pants too short, the shoulders tight and uncomfortable.

A sudden suspicion that all of his future clothes would be of the same discount variety disturbed Ben in a way that Mort’s obscene proposal and his ramshackle office and the half-conscious girl on the sofa never could. And he thought of his mother, selling herself to the textile mills back home, coughing up wool fibers as she lay awake in bed at night. And his sisters, resigned to squalid apartments and crowded schools, biding their time until the local thugs came knocking. And then it’d be babies and black eyes and government food coupons for them.

“This is a pretty standard deal I’m offering you,” Mort pressed. “Ever heard of Little Anthony and the Imperials? Ben E. King? What about the Platters? Well, they all send their Uncle Mort little green presents every month.”

Ben looked up and nodded. “Okay, Mr. Peters.”

“Okay what, Benny?”

“I’d like you to help me. To call your friend and see if I can make a record.”

Mort brought his hands together with a loud clap. “I knew you were smart, Benny. We’re going to do great things together, you and me.”

“I’ll work hard, Mr. Peters, do my best.”

“Oh, I have no doubt of that, Benny. No doubt at all.”

Ben smiled, more easily now. “When do I sign the papers?”

“Papers?”

“Well, the contract. Don’t I have to sign something? To make it legal?”

Mort stood and walked around the desk. He leaned against it, and his sizable ass shifted a stack of envelopes onto the floor. His lips twisted into a strange expression, one that made Ben recoil a bit.

“I don’t believe in contracts. Contracts attract lawyers, and to me lawyers are about the lowest form of life there is. What I believe in, Benny, is leverage.”

Ben fussed with the tear in his pants. ‘’Leverage?”

Mort shifted his weight, knocking more clutter off the desk. “Yes, leverage. Do you know what leverage means, Benny?”

“I suppose I don’t, Mr. Peters.”

“Leverage, son, is what keeps men honest. Leverage is the thing that makes a man think twice before he does something that could harm his business relationships. It preserves the big picture. Do you understand?”

“I think so, sir. It’s like an invisible person tapping you on the shoulder when you’re about to do something wrong.”

“Yes! Yes, Benny. You’ve got it right. I knew you were a smart boy. And leverage can be a lot of things. For some people it’s the idea of God and going to hell if they drink or have sex before they’re married. And for others it’s the thought of their kids starving if they don’t get up and go to work every day. I guess another word for it is fear. Fear, Benny. It keeps things moving. Fear is the great motivator.

“I’ll be honest, Benny. I figured you for a no-show after an hour passed and you still hadn’t walked in. I’m delighted I was wrong, of course. But by the time you arrived, I’d already moved onto my next appointment.”

Mort walked to the door next to the filing cabinets, keeping his eyes on Ben. His odd grin had changed to an expression of cold contemplation.

Ben stared back. The grim thoughts that had been gathering in head were now fully united and threatening to riot. He gripped the armrests and began to hoist himself out of the chair, slowly. Mort stuck out a chubby finger and motioned for him to sit. Ben hesitated, then sank back down.

“I’m actually glad it worked out this way,” Mort said. He turned the doorknob. “There’s something you should see.”

Mort pushed the door open.

For a moment Ben thought it was his old man in that back room. The light was dim enough to cast the figure into a passable specter of his dead father. The dark fellow sat on an upturned wastebasket, his long legs stretched out in front of him. He stood and stepped into the light of the office, and his hunched shoulders and flat, intimidating facial features dispelled the momentary hallucination. He wore a white tank top decorated with a single bloody handprint. His steps rattled the stacks of reel-to-reel tapes as he walked forward.

Mort looked up at the large man, beaming, as though he were gazing upon the sudden animation of his own personal Frankenstein.

“Benny, this is Joe.”

Joe nodded.

“Joe handles grievances within my stable of employees,” Mort continued. “In other words, I send him out to apply leverage when necessary. Right, Joe?”

The corner of Joe’s mouth lifted in a terrible half-smile.

“How long have we been together now, Joe? Six years?” He clapped Joe on the back. “Joe here was just like you, Benny. Poor boy from a poor neighborhood. Unfortunately, he doesn’t possess your golden throat. But he has excelled in other areas.” He hitched a thumb at the back room. “Joe, if you would.”

Joe reentered the back room.

Ben’s line of sight was such that he could see only a couple feet inside the door, but from the sound of Joe’s fading footsteps, he could tell it was a large room, or at least very long. Things went silent for a moment and then a series of loud thuds ensued, as if heavy objects were being tossed around. Soon the clopping of Joe’s boots resumed, accompanied by new footsteps, ones that were closely-spaced and erratic, like the shambling gaits of a couple drunkards.

Joe came out, pulling two people by the hair, one in each hand. They were an old Asian couple, a man and a woman, and they looked to Ben like they’d gone through one of the industrial wool presses his mother labored over back home.

The woman’s eyes were no more than slits buried inside two swollen purple rings. One of her small hands pawed at Joe’s, trying to untangle his long fingers from her hair.

The man’s eyes were unharmed, but they possessed a vacant, detached stare. His clothes hung from his slight frame in tears and tatters. His mouth was a bloody smudge, and his bottom teeth—yellow and crooked—were visible through his busted lips.

The man’s legs buckled and he fell to his knees, pulling Joe forward. Joe yanked him up by his hair, and the man uttered a gurgled moan.

Mort snickered. “You do enjoy your work, don’t you Joe?” He stepped forward and grabbed the woman’s chin. He moved it from side to side, examining her beaten face. “Good golly, Miss Molly.” He pushed her away and wiped his hand on the front of her shirt.

“Benny,” Mort said, “meet Mr. and Mrs. Nguyen. They are the proprietors of the salon downstairs.”

Mr. Nguyen looked up at Ben. His split lips quivered.

Mort nodded. Joe released Mr. Nguyen, taking away several black hairs in his greasy palm.

Mr. Nguyen ran to the sofa and fell to his knees. He took the girl’s head in his hands and began to cry. He brought his face to hers and whispered something through hitching sobs.

Mort walked over to the sofa.

“And I never did introduce you to their daughter, Benny. This sweet little thing is Anh.” He knelt down and lifted one of Anh’s eyelids. “Can you say hello to Benny?”

A bubble formed at Anh’s lips. Mort popped it with one of his fingers. “Guess not. That’s okay. You rest.”

Mort stood and walked over to Joe. “Where’s the boy? Bring the boy out here. He’s missing all the fun.”

Joe shook his head.

Mort pushed past him and went into the back room. He returned a moment later, running a hand through his greasy hair.

“Okay, what happened?” he said, placing a hand on Joe’s shoulder.

Joe shrugged. “Things happen, Mr. Peters. He got a little antsy when I started in on the woman.” He glanced at Ben, then turned back to Mort. “He tried to bite me.”

“Bite you?” Mort said, staring up into Joe’s face. A beat of silence, and then he began to laugh, mad gales that shook the flimsy walls.

Joe began to laugh as well, girlish titters that clashed with his mean face and massive frame.

“See, Benny,” Mort said through dissipating laughter. “These are the dismal results when leverage is ignored. You see, Mr. and Mrs. Nguyen were hiding money from me.”

“No,” Mrs. Nguyen pleaded. She stepped forward, grasping blindly at the air, and bumped into Mort’s desk. She uttered a weak cry and fell to the floor. “No, we don’t hide money,” she continued from her place on the filthy carpet. “Don’t hide money. Don’t hide money!”

Mort motioned, and Joe pulled Mrs. Nguyen up by her shirt collar.

“Yes, you were hiding money,” Mort said. “You and your husband. Plenty of it, too.” He walked behind Ben and placed his hands on his shoulders. “Benny, I like to believe I can see the potential in people. People like yourself. And Joe there. I saw potential in Mr. and Mrs. Nguyen as well, which is why I helped them get established. They needed a helping hand, so I gave it to them. And I made the terms of our arrangement very clear. It’s the same as ours, Benny. Seventy-five percent.”

Mr. Nguyen stood abruptly. “We give you your money. On time, all time.”

Joe came around the desk and seized Mr. Nguyen by the arm.

“The Nguyens started coming up short about six months ago,” Mort continued. I’m talking about a steep decline in revenue. So I hired one of my personal accountants to comb through their books. And sure enough, there was a sizable chunk of hidden cash, an amount that entitled me to thousands more than what I’d been paid.”

“Fook…” Mr. Nguyen muttered. His face was now a twisted mask of unmitigated rage. “Fook you!” He spat a wad of phlegm; it landed on the left leg of Mort’s gabardine trousers.

Mort regarded the lunger briefly. He smiled, lifted his head, and then took a running step forward, driving his meaty fist into Mr. Nguyen’s chin. Mr. Nguyen’s head rocked back and slammed into the wall, then lolled forward. A couple of teeth fell through his mangled lips and rolled across the carpet.

Mort ran his tongue over his knuckles. “Oh, Benny, the boss’s work is never done.” He leaned against the desk as he had before, rivulets of sweat trailing down his flushed cheeks. “Yes, I’m glad you’re seeing all this. Maybe if I’d offered the Nguyens a similar demonstration, this whole nasty scene could have been avoided. Maybe they thought I was kidding, or maybe they just thought I was soft. Either way, here we are. And we’re all losers in this to some extent, Benny. The Nguyens have lost a son, and I’ve lost a sweet plum in that salon downstairs. There’s simply no going back now. The trust has been irreparably damaged.”

Ben sank into his chair until the vertical wooden slats dug into his back. He’d been biting the inside of his lip to stifle the onset of tears, and now he tasted metal on his tongue, hot and electric. His shirt collar suddenly felt like hands pressing into his sweaty flesh, and he loosened his tie some more.

“Now, Benny,” Mort said, crossing his arms at his chest, “you need to understand the terms of our agreement. I don’t want any boo-hooing later on. You are now in my employ. Which means I’m responsible for you. I will put you in touch with the right people, grease the right palms, whatever is needed to give you the best shot at success. With me so far?”

Ben nodded, flinching as he did so, as if any sudden movement might trigger some internal explosion within his new business partner.

“Good. That’s good. But now you have a responsibility to me, also. And that responsibility is seventy-five percent. Now and forever. I’ll put it plainly, Benny. If for some reason this music thing doesn’t work out—you come down with throat cancer or you marry your first cousin and the world decides it wants nothing to do with you anymore—I still expect my cut. Every month. Whether you’re bagging groceries or humping pallets on some loading dock, I get my seventy-five percent. There will be no leniency in this regard. The Nguyens here can attest to that.”

Mr. Nguyen moaned pitifully, held up now by Joe’s huge hands. His feet danced lightly over the carpet like the feet of a marionette.

Mrs. Nguyen clutched one of the tall filing cabinets, her small fingers trailing ribbons of blood along the gray metal surface. Her lips trembled over inaudible incantations, private messages from her shocked and ravaged mind.

“Leverage can vary, but it usually comes down to family. And you’re not unique, Benny. So here’s what’s what. Should you fail me, should you grow tired of our agreement and decide you’re simply going to walk away, you best pause and reconsider. My memory is long. And so is my reach. I’ll have Joe pay your mother a visit. Then he’ll stop in and see your sisters. Perhaps I’ll tag along for the latter. That might be fun.”

“No,” Ben muttered. The tears came now, nearly exploded from the corners of his eyes. His face went all tingly, as if he’d just awoken suddenly from a long nap. “I changed my mind. I’ll go home. I don’t want anything.”

Mort squatted and gripped Ben’s knees. “Look at me, Benny.” Ben pulled away from him and turned sideways in the chair. “Ben. Let’s not do this.”

Ben broke for the door. Joe cut him off, pulling him into a tight embrace and dragging him back to the desk. He turned him to face Mort.

“You’re in now, and there’s no getting out.” Mort’s stubbly chin pressed into Ben’s soft, hairless cheek. “You need to reconcile yourself to that. Remember your mother and sisters. I’ll make you watch while Joe takes them apart piece by piece. I’ll string their tongues onto a necklace and make you wear it.”

Ben looked into Mort’s eyes through a curtain of hot tears. They looked small and dark like drops of oil, the eyes of a rodent, and he could see vast frontiers of nothingness behind them.

Then a gray haze began to wash over Ben’s vision, a preamble to unconsciousness, and Mort seemed to float away toward the ceiling.

Ben was returned to a state of complete lucidity as he struck the floor. He landed on his tailbone; a frenzy of pain raced up his back and spread across his shoulders. He opened his eyes and saw an upside-down Joe falling against Mort’s desk.

Ben rolled toward the sofa and didn’t stop until he bumped up against it. He sat up and wiped the film of tears from his eyes. His vision cleared in time to see Joe hit the floor, face-down. The handle of Mort’s letter opener jutted from his back like some shiny, misplaced appendage. A young man stood over him, his face a gruesome deconstruction, the side of his head a riot of snarled hair and glistening, torn-up scalp.

A loud crash. Ben pulled his gaze away from the ghastly newcomer and saw that Mort had yanked one of the desk drawers off its track and dumped its contents onto the floor. Mort dug crazily through an avalanche of assorted junk: staplers and fountain pens and plastic tins full of rubber bands. He finally pulled a gun from the pile. Ben recognized it as a Colt Cobra, a gun he’d seen Lee Marvin run with on episodes of M Squad. Mort checked the chambers and then held it out in front of him. The revolver shook in his plump hands. He rose to his feet clumsily, almost tripping over the scatter of office supplies. His eyes darted from side to side, frantic, looking for the deformed assailant who’d suddenly winked out of sight.

It wouldn’t occur to Ben until many years later, during one of those private and painful moments when the past ambushes you with images of things you’d rather forget, that it had been Mort’s complacency that killed him. Mort had grown so accustomed to being in control, so comfortable with his own concept of leverage, that he’d tucked his gun away in a drawer. Had he been carrying the gun, or had it strapped under his desk where it could be easily reached, things would have gone down differently. Instead, the precious few moments he wasted locating his piece allowed the Nguyen boy enough time to haul the letter opener out of Joe’s back and walk around the desk, unnoticed.

Two inches of gold-plated steel emerged from the front of Mort’s throat as he stood there holding the Cobra. A slow dribble of blood ran down the tip of the blade and onto his Hush Puppies. The gun fell to the floor. He brought a hand up to his neck and poked the tip of the letter opener with his index finger. His eyes rolled back and he fell forward. His arm swept a stack of reel-to-reel tapes on his way down. He hit the floor with a heavy thud, the tapes cascading over his lifeless body.

Ben got to his feet, shaking, barely able to keep his balance, and crept to the office door.

The Nguyen boy bent down and grabbed the revolver. He pointed it at Ben. “Stay,” he said, his words slurred and wet-sounding. “Stay there.”

Ben raised one hand slowly. He used the other to hold up his pants; he’d wet himself, and now they hung low and heavy on his skinny waist. He took a couple steps backward, his socks squishing inside his shoes.

Mr. Nguyen approached his son and placed a hand on the barrel of the gun, lowering it. He said something in Vietnamese and then he and his boy turned and stared at Ben.

Mrs. Nguyen staggered toward the sound of her son’s voice. She reached out, groping feebly. The boy took her by the arm and drew her close. Then he dropped the gun and led his mother over to the sofa. They knelt beside Anh. She managed to open one eye and mumble something to her mother and brother. Mr. Nguyen joined them. Together they held each other and cried.

Ben opened the door and stood there, watching the small family. After a moment he walked out of the room, holding up his soggy pants. He passed the secretary’s desk, then stopped. He turned his head and looked up at the photos on the wall. Young men and women—kids, really—not much older than him. He studied their glowing faces, their pressed suits and sequin dresses.

He went back into Mort’s office. The Nguyens were helping Anh to her feet, keeping the Indian blanket cinched tight around her tiny body. They stared at Ben miserably, as if maybe their nightmare wasn’t over. Ben walked over to Mort’s desk, stepping around Joe and the blood that had begun to saturate the carpet. He sifted through some papers and grabbed the index card Mort had tempted him with. He folded it and slid it into his jacket pocket. He took one last look at Mort, now just a chubby leg and a tuft of greasy hair sticking out of a mountain of demo tapes.

Ben walked back to the bus station and stretched out on one of the wooden benches next to the ticket counter. He was shaking and smelled of piss and sweat, and more than a few people eyed him suspiciously. He lay there in silence and looked up at the large clock hanging above a row of pay phones. His bus wasn’t scheduled to leave for another two hours. He wondered if he should go into the bathroom and clean up.

Instead he stood and pulled the folded index card from his pocket.

He walked over to one of the pay phones. He hesitated, then lifted the receiver from its cradle. He fished a handful of wet change from his pocket and fed the coin slot.

He took a deep breath and dialed.

&&&

Taken from RollingStone.com, September 14, 2013

Benjamin Turner, Soul and R & B Icon, Dead at 70

by Robin Myers

Singer Benjamin Turner, best known for his string of Motown hits in the 1960s, died in a Los Angeles hospital after a short illness, according to his wife Mary, The Associated Press reports. He was 70.

A Pittsburgh native, Turner was introduced to Motown founder Berry Gordy in 1961 by legendary music agent Merle Hirsch. Gordy signed Turner after a brief audition and the resulting partnership yielded several classics including “Spin Me ‘round One More Time,” “Feel Like Being with You,” and “Mr. Lonely Heart.”

Turner’s popularity waned after his departure from Motown in 1972, though he continued to perform sporadically for the next several years.

His career experienced a brief renaissance in 1985 when he collaborated with then newcomer Madonna on the Top 10 dance hit “Take Me to the Club.” He reentered the spotlight again in 1993 when he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio. Turner’s emotional speech at the induction ceremony drew a ten-minute standing ovation and is widely recognized as one of the Rock Hall’s finest moments.

Turner began a second career in 1998 with the formation of his non-profit venture Helping Hands, Helping Hearts. He established the organization to assist minorities with career training and education funding. “Of all the things I’ve done in my life, this foundation is what I’m most proud of,” Turner stated during a 2002 Rolling Stone interview. “I come from a place where people of color are often forced into the wrong decisions in order to survive. It doesn’t have to be that way. I want to do what I can to fix that.”

Mary Turner said funeral arrangements are still incomplete, though a service is expected to be held sometime next week in Los Angeles.

* * * * THE END * * * *

Copyright Paul Edmonds 2014

Pretty good noir.